Did QE cause bank failures?

Quantitative easing's explicit intent was to push banks to take interest rate risk

One aspect of the failures of Silicon Valley Bank (SIVB) and Signature Bank (SBNY) that has not received enough attention is the potential role of the Federal Reserve’s unconventional policies of the last decade. By forcing banks to hold increasing shares of unprofitable assets, the Fed unintentionally pushed banks to take greater risks elsewhere to maintain profitability. Many banks responded – encouraged by the Fed’s “forward guidance” – by taking greater interest rate risk that resulted in large losses when the Fed was latter forced to rapidly hike rates as inflation slipped out of control. To appreciate how the Fed’s policies since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) may have contributed to the failures of SIVB and SBNY, one needs to understand how money is created and how monetary policy works.

Contrary to popular belief, central banks like the Fed do not create money; you do. Whenever you take out a loan from a bank – a mortgage, car loan, business loan, or charge a credit card – the bank simply creates the money from thin air and credits it to your account. Banks are legally licensed to do this up to a limit: for every dollar of loans they extend to households and businesses, banks must hold a fraction of that value in reserves at the central bank. Reserves are a special “inside money” of the banking system, created by the central bank, that only banks can access. By controlling the amount of reserves in the banking system, central banks like the Fed limit banks’ lending and thus money creation in the economy.

In normal times, the Fed, like most central banks, manages the level of reserves (and thus the money supply) by targeting interest rates. When the economy is running hot, loan demand picks up and interest rates naturally begin to rise as banks hit their reserve lending limits. The opposite occurs when the economy cools down. The Fed manages the rate of money and economic growth by targeting the interest rate at which banks borrow and lend reserves to each other, the Federal funds rate. When it begins to rise above target, the Fed adds reserves to the system by buying bonds from banks, paying them with reserves. If the Fed funds rate falls below target, it sells bonds, destroying reserves. If the Fed thinks the economy is too hot, it raises its target for the Fed funds rate and lowers it when the economy is too cool.

But the post-GFC period has not been normal. The Fed cut interest rates to zero percent in response to the crisis and the economy still wasn’t growing fast enough to keep inflation at their desired 2% rate. With the Fed unable to take interest rates below zero, the Fed tried to stimulate the economy with an experimental policy called “quantitative easing” (QE): huge purchases of government bonds that injected far more reserves – “excess reserves” – than banks needed to make loans demanded by the economy. Recall that reserves define the legal maximum of bank lending, but that household and business demand determine its minimum and consequently money creation. As the famed British economist John Maynard Keynes observed, monetary policy at the zero lower bound is “like pushing on a string.” Thus, while QE has often been called “money printing”, no new money is created, it only piles reserves on banks balance sheets.1

This creates a profitability problem for banks. Banks make money by borrowing from depositors at low interest rates and lending to households and businesses at higher interest rates. The spread between the cost of banks’ liabilities and what they earn on their assets is called a net interest margin (NIM). Bank’ profits are roughly equal to the value of their assets multiplied by their NIM and thus directly proportional to both. When loan demand falls, so does bank profitability. QE makes the problem worse because reserves are assets for banks: assets that are paying zero precisely when banks face weak borrowing demand for loans. As zero-yielding reserves increase as a proportion of assets, banks’ NIMs fall, further crushing their profitability.

The only way for banks to maintain profitability amid QE’s NIM suppression is to pursue higher-returning – and thus higher-risk – assets in the rest of their portfolio. Banks can do this by taking either credit risk or interest rate risk. Credit risk involves lending to borrowers who are more likely to default. Interest rate risk involves making longer maturity loans — or buying long-dated bonds — whose value falls when interest rates rise.

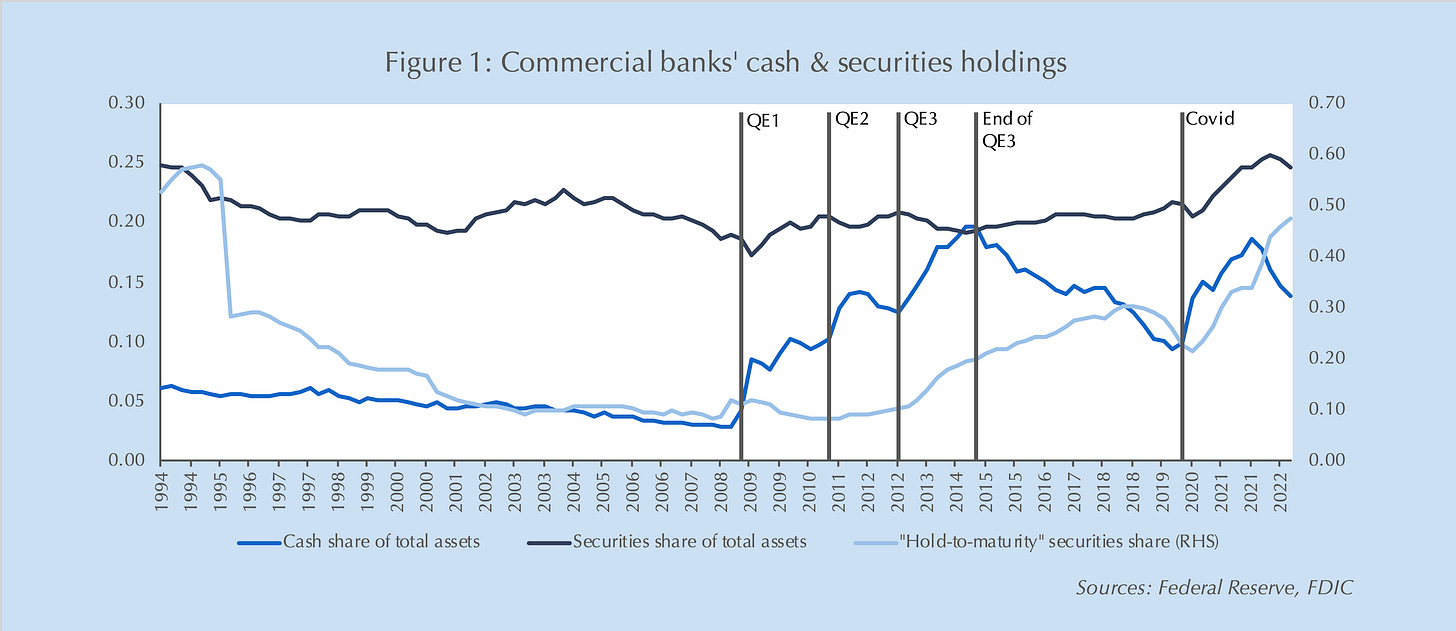

While credit risk is harder to observe in aggregate data, we can clearly see the effects of QE on banks’ asset composition and interest rate risk. Figure 1 shows US-chartered commercial banks’ reserves and securities (bond) holdings as a share of total assets. The reserve share increased markedly during the three rounds of post-GFC QE and during the post-Covid QE program. The securities share increased much more during the latter. Also displayed, against the right axis, is the “hold-to-maturity” share of securities; or bonds that banks, for accounting purposes, commit to hold until they mature. This is an indirect measure of banks’ willingness to take interest rate risk.

The failures of SIVB and SBNY were directly attributable to excessive interest rate risk and specifically their large hold-to-maturity books. As inflation took off beginning in 2021 and the Fed was forced to pivot from its massive post-Covid QE program to aggressive rate hikes last year, both banks incurred large losses on their bond holdings. Both SIVB and SBNY were particularly exposed to the rise in rates as their deposit bases were both concentrated and highly sensitive to rising interest rates, forcing them to recognize the losses on their bonds as their deposits fled. Poor risk management may have made SIVB and SBNY weak links in the system, but they were not alone in taking excessive interest rate risk as evidenced by both Figure 1 and reports of extensive bond losses across the banking system.

And who can blame banks for doing so: they were encouraged to by the same central banks that were loading them with non-profitable reserves. In a vainglorious effort to raise inflation, central banks across the globe, led by the Fed, also engaged in “forward guidance”, verbal commitments to and forecasts of ultra-low interest rates for the foreseeable future. The aim of this guidance was precisely to nudge banks and other investors to buy more longer-dated bonds and increase their interest rate risk in the hope that lower long-term interest rates would stimulate inflation. Whether QE or forward guidance actually created inflation remains debatable, but without question it left the banks’ balance sheets wrong footed when inflation finally did arrive and the Fed raised rates aggressively in response.

SIVB’s and SBNY’s collapses clearly stem from poor risk management. But as legislators, policymakers and regulators conduct post mortems like Fed Vice Chair Michael Barr’s recently announced investigation into bank failures, an honest assessment of how the experimental monetary policies of the last decade may have contributed to systemic risk is required. In a fair cost-benefit analysis, did those policies do more long-term harm than short-run good?

For markets, the focus should be on what types of risk banks took in response to the decade-long repression of NIMs by central banks: excessive interest rate risk as in the cases of SIVB and SBNY, or excessive credit risk as appears to be the case for Credit Suisse? If the former, the Fed’s newly launched term-lending facility likely will provide banks with the necessary liquidity to grow out of losses in their engorged “hold-to-maturity” bond books. That bodes well for individual banks, their depositors and the economy. Banks that took more credit risk present a trickier assessment. If their credit risk was concentrated among borrowers that are overly dependent on low interest rates or tied to globalization that now is in reverse, they may face serious problems even if the broader economy does well (see my assessment of 2023’s likely credit problems in Debt reality versus perceptions). If credit risk was less concentrated, then these problems may not manifest in banks until a recession finally rolls around.

This free article is made available to all to highlight its public policy points. Thematic Markets research provides differentiated strategic insights into the global political economy and markets based on rigorous fundamental research. If you enjoyed this article and found it thought provoking, please consider subscribing.

I am simplifying for exposition. In reality, central banks buy bonds from non-bank dealers who do not have access reserves but receive (newly created) money from their banks who, in turn, receive reserves from the central bank. But this is temporary. Since the economy wasn’t demanding any new money, the dealer (or someone they transact with) uses the newly created money to pay off loans, removing it from the economy in the process and returning the money supply to its pre-QE level.