Global Entropy: Enter the dragons

Geopolitical disorder emerges as the greatest economic threat

In late 2019, my high conviction in US outperformance, held since 2014, began to erode as I perceived increasing risk of high-impact, unpredictable events. By February 2020, adding a strange, emergent respiratory disease from China to my list, I wrote:

“The world is awash with difficult-to-quantify risks associated with tectonic shifts in politics within and between countries, climate change and new technologies, and their impact on value chains, economic relationships, and disease management in an era of hyperglobalisation.”1

That statement may be truer today than it was just before Covid upended the world. Conditional on there being no large-magnitude, “exogenous” disruptions (pandemics, wars, comets…), I remain confident of Localization-driven US outperformance, higher-for-longer interest rates, underperformance of and significant macro-credit risks in both Europe and emerging markets, and long-run persistence of “China’s Age of Malaise”.

But the key word is conditional. The world stands on the precipice of a calamity with the potential to be far more disruptive, costly and more deadly than Covid. Global entropy – the two-decade old dissolution of the post-World War II liberal order (PWLO) – threatens to tip into a Complexity cascade that brings down the entire edifice with frightening speed and potentially catastrophic effects. Whether the world stumbles over the precipice into a Complexity cascade and what events will unfold as a result, define Uncertainty: non-quantifiable risk. Yet, the implications are so profound – not just for asset markets – and the signals of its rising likelihood so clear, that it now is impossible to ignore in portfolio management and strategic decision making.

This is the first in a four part series on Global entropy, its economic and financial implications, its potential for a rapid chaotic conclusion, and the global political economy and financial architecture that is likely to emerge from it. Here in Part I – made available free for all readers – I provide a framework to understand the forces driving Global entropy, what the geopolitical endgame looks like, why we now are at risk of nonlinear acceleration, and what risks that might present.

The remainder of the series is for paid subscribers only. Part II will outline an investment strategy to protect against the risks presented by a Complexity cascade of rapid dissolution of the PWLO. Part III explains why, despite Global entropy‘s complex endgame, the global economy is likely to take a semi-fluid bipolar form. Finally, Part IV describes the bifurcation – not diversification – of global finance that already underway, and why that likely will lead to the emergence of durable, blockchain-based payments system bridging the economic bipoles.

Key insights

Global entropy, the two-decade old dissolution of the post-World War II liberal order (PWLO), has advanced far enough that it now faces a dangerous tipping point of potential disorderly acceleration towards a chaotic endgame.

The base case for Global entropy is evolution to a bipolar order with multiple regional powers playing off the Western bipole against its opposite, the Sino-Russian duo-pole.

The bipolarity will be reinforced by increasing technological dominance of the Anglo-sphere and China within a bifurcated system of information and export controls and mutually reinforcing network effects. The “great games” of international relations will be bifurcated technology networks and geostrategic competition for mineral resources. As such, supply security and repulsion from the West will be the glue of the Sino-Russian relationship.

But there exists a significant but non-quantifiable potential for Global entropy to slip into a Complexity cascade of chaotic Uncertainty with a more fragmented and fragile global order resulting.

Cultural differences will play an outsized role in the path Global entropy takes. Since the 1990s, Western diplomacy has become increasingly moralistic and simultaneously blind to the chasm between its own values and most of the rest of the world. China and Russia are challenging its global leadership and the PWLO by exploiting that chasm to propose a world order based on sovereign rights, making cultural values and rights of self-determination the battleground for a new world order.

With Western political, economic and military ascendency past their respective peaks, cultural divisions are more visibly being used as weapons to fracture the PWLO.

The risks of catastrophic failure of the PWLO and a Complexity cascade hinge on the ability of adversaries of the PWLO to exploit differences in cultural values and overwhelm the US and its allies with geopolitical fire fighting.

Disorder & nonlinearity as natural states

Entropy is a concept from physics that any system, left alone will tend towards disorder. Complex structures like human organizations are no different. By Global entropy, a major Theme in the global political economy, I am referring to the natural dissolution of the “rules-based,” post-War liberal order (PWLO) established by the US and its Western allies at the end of World War II. The PWLO has persistently eroded over the last three decades due to a series of Western missteps combined with the natural tendency of challengers to arise within a complex system like the global political economy.

Complex systems, like nation states and international orders, are nonlinear and can rise or fall with surprising timing and rapidity. Global entropy is now well advanced, and in my view, the PWLO stands at a precipice where a wrong step could result in rapid, complete dissolution. To understand how and why this could occur, and what might result from nonlinear demise, I begin with a framework for international relations and a history Global entropy since the PWLO’s peak.

The glue of international relations

Socio-political entities like nation states, supra-national entities, and international orders all are held together by three forms of glue: power (threat of force), wealth (allocation of scare resources) and myth (culture, religion, ethnic or linguistic ties).2 The most durable socio-political entities are build on all three. But larger, multi-group socio-political entities face a problem since myths tend to be grounded in a shared history, language, religion or culture. In these cases, myths may be more likely to obstruct cohesion than bind peoples together. As a result, multi-ethnic empires and, especially, international orders have typically relied more on power and wealth, making them less durable than nation-states (or tribes) that can rely on all three socio-political adhesives.

A central pillar to my thesis is that an important contributor to Global entropy and its future pace is a mistaken belief by the West that its own socio-political myths are internationally shared. As a result, the West over relies on myth to maintain the PWLO and is blind to others’ antipathy the myths it promotes, particularly, its conception of “universal human rights”. The gap between the West’s perceptions and reality provides and opening for its adversaries to exploit in tearing down the PWLO.

Global entropy, the story thus far

The US-led PWLO is exceptional in history and was enabled by unique circumstances: a world war that left the US head and shoulders above all global challengers. In its aftermath, the US was by far the largest economy, the most powerful military, master of the seas, and its universities and research laboratories were the primary source of innovation in the world (see Solved: Drivers of the dollar cycle). No other nation or empire in human history was so globally dominant. For four decades, the Soviet Union’s nuclear capabilities created a bipolar international political order, but economically and culturally the US was without equal. Within that context, the US was able to impose and sustain a world order of its own design. Access to US markets, for those that participated, was the key to rapid income growth as pioneered by Japan and Germany, and later copied by Asia’s “Tigers”, while the US Navy kept the seas free for commerce, and the US military and alliance network policed any would-be disruptors of Pax Americana.

Apex neoliberalism: the beginning of the end

Yet arrogance and time, the greatest enemy of order (and friend of entropy), would eventually bring about change. Time allows for supplicants to learn, grow and eventually challenge the master. Indeed, this was intrinsic to the design of the PWLO: the US Marshall Plan, US AID, and post-War international institutions like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) were created to facilitate the growth and rebirth of destroyed and developing nations, while the United Nations (UN), World Trade Organization (WTO), and International Criminal Court were created to channel would-be challengers through an institutional bureaucracy and systems of rules to avoid more costly state-to-state conflicts. However, as a result, the entire system increasingly came to rely on its own creation myth: that the rules underlying the new international governance structures and bureaucracy were “universal values” accepted by all.

While US power and wealth remained pre-eminent, the PWLO myth could be supported, but unfortunately for PWLO and the West, Apex neoliberalism was fast approaching and with it the blind arrogance of its adherents. The three pillars of Western power — the PWLO myth, economic dominance, and military superiority — peaked in relative terms over little more than a decade from 1991 to 2003.

Peak myth

Western international prestige peaked in 1991 with coincident fall of its only geopolitical rival, the Soviet Union, and the Gulf War’s expulsion of Iraq from Kuwait by a US-led coalition of 42 nations sanctioned by the UN and even the Arab League. Seemingly democracy had triumphed, recidivist powers were in decline, the “rules-based order” ruled international relations, “universal human rights” were accepted by all, and “The End of History” was declared.3 The reality, as time would prove, was quite different: many emerging markets superficially adopted Western liberalism to access the rich US and European markets; others, like the former East Bloc as noted by Branko Milanvic, did so as “revolutions of national emancipation” from centuries of rule by the Austrians, Germans, Turks, and more recently the Russians;4 while still others did so out of fear of the West’s awesome display of power in the Gulf War.

At least one country took a very different lesson: the imperative of rapid modernisation to resist the Western order or even over throw it, and the usefulness of PWLO institutions for a poor country to do so. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), having just two years earlier brutally crushed a liberal movement that threatened its rule, looked with horror at the ease with which the American military turned an army that looked very much like its own into smouldering rubble along the “Highway of Death” in just 10 hours. Chinese fears were fanned over the next two decades by increasingly values-driven Western international activism under the aegis of the PWLO, that coincidentally resulted in the humiliating (for China) accidental bombing of its Belgrade embassy in 1999 during the UN-endorsed NATO bombing campaign of Serbia.

However, Apex neoliberalism, giddy with its own success, sowed the seeds of its demise over the course of the quarter century following the Gulf War, as West, blind to the reality that others had not, deeply bought into its own myth and stretched towards imperial overreach. President Clinton’s Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright epitomized the hubris of Apex neoliberalism when she justified US international activism by stating “If we have to use force, it is because we are America. We are the indispensable nation. We stand tall. We see further into the future.”5

Under Apex neoliberalism, Western statecraft shifted from national security to moralistic, even evangelical international interventionism to uphold the Western vision of morality.6 The “War on Terror” further confused US international relations and power projection, in particular. For nearly a quarter of a century, under three separate administrations, the US led narrowing coalitions backed by increasingly tenuous PWLO legality on expeditions of regime change in Serbia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria, and conducted drone or Special Operations Force (SOF) assassinations or other extra-sovereign missions in a variety of other countries.7

Overuse and inconsistent application of a morality many other countries did not share, applied with frightening lethality by the West’s expensive, hi-tech militaries, scared, appalled and disillusioned non-aligned countries and even many allies.8 Meaningless “red lines”, flip-flopping between both allies and adversary-engagements with each administration change (2000, 2008, 2016), and a long line of body bags and failed or weak states, culminating in the disastrous and humiliating US withdrawal under fire from America’s longest war (Afghanistan) demolished what was left, if anything, of the myth holding together the PWLO…for everyone but the West.

Peak economy

Western economic power peaked with China’s accession to the WTO on 11 December 2001: the shot not heard around the world. Weaponizing the Asian development model pioneered by Japan, China industrialized and climbed the economic-value chain with unprecedented speed and scale through consumption repression and directed investment (Mercantilism (with Chinese characteristics)), and reorientation of global supply chains through uncoordinated group exchange rate repression (Chinese co-prosperity sphere) that leveraged the monstrous appetite of the US consumer. In the process, China became the literal factory floor for not only the US, but the world. China is now the second largest economy in the world, its largest official creditor, and the largest trading partner to more than 120 countries.9

This was no accident nor merely the most successful development strategy in history. With 20-20 hindsight, it appears part of a broader grand strategy to challenge the US and overturn the PWLO. By becoming the world’s factory, China’s industrial policies made both allies and adversaries alike critically dependent on it for nearly all manufactured goods, from essential medical supplies to advanced materials and technologies. The latter reflected not only extensive industrial policies but detailed, methodically designed outward-investment10 and espionage policies11 that catapulted China to the cutting edge of industrial and military technologies. China’s near monopoly production of the rare earths essential for many advanced technologies (and guided munitions) and Huawei’s leadership in 5G networking are well known, but the list of critical technologies in which China now leads or dominates — 53 of 64 in one study12 — is both staggering and reflective of at least two decades of carefully planned and executed long-term state strategy.

China’s economic and industrial policies, its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and widespread information warfare,13 appear to follow the arc of grand strategy sketched by two senior colonels in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 1999. In their book “Unrestricted Warfare”, Major General (ret.) Qiao Liang and Colonel (ret.) Wang Xiangsui advocated, as the title suggests, an unrestricted definition of warfare that extends beyond military conflict to all domains, specifically enumerating economics, politics, international law, and information.14 Although the influence, feasibility and even originality of the book’s strategy are debated15 — some argue the book merely restates Mao Zedong16 — it is hard to deny that China’s polices of the last quarter century well fit the book’s recommendations.

A 2015 speech on economic and financial policy by General Qiao, with specific examples, supports that idea that Chinese economic policies were at least partly designed with inter-state conflict in mind. A year before the Chinese renminbi achieved international recognition as a reserve currency with inclusion in the IMF’s special drawing rights (SDR) basket, General Qiao spoke before the CCP’s Central Committee, focusing his speech on economic warfare that (1) explicitly identified the BRI as an economic weapon, (2) described (his perceived) use by the US of the dollar as an economic weapon; and (3) made a case for China to pursue a reserve currency as both a countermeasure and offensive weapon.17

Peak military

With growing economic might focused on the broadest definition of warfare, challenging US military dominance was only a mater of time. That job was made easier by Apex neoliberalism’s arrogance and strategic misdirection towards international activism and the “War on Terror”. David Kilcullen dates the high-water mark of US military power precisely to 5:30am Bagdad time on 19 March 2003 when US Special Operations Forces failed to decapitate the Iraqi regime in the opening salvo of Iraq War.18 From that point onward, US superiority in expensive, hi-tech, communication-enabled, precision-guided weapons designed to fight “dragons” — strategic rival nation states with professional militaries — increasingly gave way to cheap, low-tech,19 asymmetric countermeasures of “snakes” — dispersed, non-state actors — as the latter evolved to avoid direct confrontation with the unmatched lethality of American technology.

But Dr. Kilcullen points out that the dragons were watching the snakes and learning while Apex liberalism blinded the West to the growing danger: “Western powers have acted as if they were still in a…security environment [characterized by] threats originated from weak [or] failing states and nonstate actors…[when they instead faced] a return of state-based threats and great-power military competition”. While the US was preoccupied with its War on Terror, nation building and the global financial crisis, the dragons were testing their own asymmetric strategies and advanced weapons: “liminal” or hybrid warfare just below the threshold for counter attack or with plausible deniability (e.g. poisoning dissidents in foreign nations, “little green men”, unmanned vehicles, and balloons);20 hypersonic missiles,21 fifth-generation stealth fighter jets,22 swarming autonomous vehicles (used to attack the world’s largest oil terminal),23 and loitering munitions (demonstrated with deadly effect first in Nagorno-Karabakh and lately in Ukraine).24

The dragons emerge to stretch

By the end of the noughties, the dragons began to emerge from their lairs to stretch and test their new strategies and weapons. Russia had developed its own — similarly disputed and misunderstood — version of “Unrestriced Warfare”, the “Gerasimov Doctrine”.25 To prevent NATO enlargement to Georgia and borrowing a justification of Western international activists, Russia invaded and occupied two breakaway provinces to “prevent genocide” in 2008.26 Six years later, unflagged “little green men” seized Crimea from Ukraine and held a referendum to join Russia.27 Next, Russian armed and supported separatist insurgencies in two eastern provinces of Ukraine. Then in 2016, albeit almost certainly accidentally, Russian information operations hit the mother lode with $100,000 in Facebook ads that had no discernible effect on the US election but wholly absorbed and crippled American politics for the next four years while hobbling the presidency.28

China also tested its borders in ways that flew just under the threshold for action. It started in space in 2007, blasting an unused satellite into thousands of shards with an anti-satellite missile.29 Then in 2013, it began to construct whole islands and fully militarize them from tidal rocks and shoals in the South China Sea, a vast and crucial waterway it claimed as sovereign waters.30

The dragons also began to challenge both the PWLO myth and Western leadership. In 2013, the Obama administration opened the door in 2013 by inviting Russia to help enforce its “red line” regarding chemical weapons use in Syria’s civil war. After the US then failed to act on violation of its own red line, in 2015, Russia intervened directly in support of the Assad regime, against the expressed Western policy of regime change.31 The Syrian saga simultaneously boosted Russian prestige as an alternative to the PWLO while catastrophically undermining US and Western credibility.32

China instead offered carrots, but through its own alternative institutions rather than those of the PWLO. Its first salvo was to launch a competitor to the Washington-based, Bretton Woods-era Asian Development Bank with the establishment of the Beijing-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.33 Even before founding the AIIB, China engaged in a massive bilateral official lending program that has made it the world’s largest official lender (that has recently put it in conflict with the Paris Club of other official lenders in debt restructurings in Ghana and Sri Lanka). But the official numbers hide much of China’s direct aid and lending: one accounting reveals $841 billion of lending and aid associated with more than 13,000 projects in 145 countries since 2000.34

With greater ambition, China launched the BRI in 2013. The BRI was structured as a development aid and trade promotion initiative that oriented development towards integration with China and was explicitly shaped as an alternative to Western mechanisms like the IMF and World Bank. In doing so, the BRI simultaneously attempted to supplant the PWLO with China’s own soft power while creating an economic and physical infrastructure that enhanced China’s economic power through trade links, and its military power through a string of deep-water naval ports and land-based transit mechanisms for critical minerals.35

The US finally noticed the newly flexing dragons with the election of Donald Trump in 2016. No friend of the PWLO himself, President Trump arguably helped further undermine it by unsettling allies and displaying open hostility to its institutions. But his administration’s foreign policy clearly broke with moralistic global policing and shifted instead to a realist policy of “offshore balancing” (even if never formally articulated or perhaps understood as such by President Trump).36 The shift to offshore balancing implicitly recognized the need to preserve US strength for conflict with strategic rivals by shifting from direct engagement “onshore” in less-vital conflicts to use of local proxies (e.g. the Kurds and Israelis in Syria)37 and gunboat diplomacy (e.g. the drone assassination of Iranian Quds Force leader Suleimani).38 But more enduringly — though it took the election of Joe Biden for the US establishment to grudgingly accept it — President Trump identified China as an irreducible strategic rival of the US.

But by then, it was too late: the myth of the US-led PWLO had been shattered, US military and economic power were no longer invincible, and Global entropy was visible everywhere. Then the dragons began to roar.

The end of the beginning: the dragons roar

By the start of the Biden administration, China already had completed a multi-nodal platform for anti-access/area denial that is thought to be fully effective through the “first island chain” of the Western Pacific.39 The centerpiece of its capabilities are overwhelming land-based intermediate-range, ballistic missiles (IRBMs), many capable of precision targeting, hypersonic manoeuvrability and carrying either conventional or nuclear payloads. The most advanced of these, the DF-17, has the range to strike through the second island chain.40 Within the first island chain China has built a fleet of “unsinkable aircraft carrier” man-made islands to complement the world’s largest navy (by number of ships); the largest merchant marine and “fishing” fleets, has newly acquired or is developing deep-water ports extending around the Indian Ocean to Djibouti on the Arabian Sea, and is in negotiations with Equatorial Guinea for an Atlantic Ocean base.41

Increasingly confident that it now could deter US naval power, and likely emboldened by the disastrous US withdrawal from Afghanistan, Chinese rhetoric has became far more bellicose and coupled with equally aggressive actions. President Xi dropped any pretence of Deng Xiaoping’s “hide your strength and bide your time” policy. As early as the 2017 Communist Party Congress, President Xi declared a “new era” in which China should take “center stage in the world to make a greater contribution to human kind.”42 More recently, President Xi was even more explicit on what this meant, telling Chinese soldiers to prepare for war as “the East is rising and the West is declining.”43 The carrots of official lending and BRI remain on offer, but the dragons claws now are more clearly bared in “wolf-warrior” diplomacy, especially for those perceived to violate its “One China” policy. China severed “circuit-breaker” high-level military dialogue with the US in punishment for House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, and has not reinitiated them despite US requests, in part to keep the US off balance.44

In keeping with the sharpening of its rhetoric, Chinese territorial expansion also has become more aggressive. In addition to daily incursions into Taiwanese airspace and territorial waters by the Chinese military, China also has staged multiple large-scale naval exercises just off Taiwan, including joint exercises with the Russian navy.45 In the South China Sea, harassment of non-Chinese vessels by Chinese “fishing boats” has more recently escalated to ramming by Chinese coast guard vessels.46 But perhaps most aggressively, while the world was preoccupied with Covid, Chinese troops pushed forward the line of control in the Galwan Valley, in a disputed area of the Himalayas, killing 20 Indian troops in the process.47

The Russian roar was heard even louder. Dispensing with deniable attacks by unflagged little green men and ethnic Russian separatists, Russia launched a full-scale (and fully flagged) invasion of Ukraine in 2022 in a war of attrition and proxy war with the West that continues today.

On the precipice: Culture & Complexity

The dragons have fully emerged and shown there is little that American firepower, economic sanctions or moral suasion can do to contain them. Global entropy is well underway and the only questions remaining are how rapidly or disruptively the final vestiges of the PWLO collapse, and what emerges in its place.

Somewhat paradoxically, I submit that the answers to these questions hinge on socio-political myths, or culture. Both power and wealth — the strongest socio-political adhesives at the international relations level — are undergoing technological revolutions that will leave them in flux perhaps for decades. Localization is upending the global economic order, while the rapid evolution of military capabilities and strategies are doing the same for state power projection. The key driver of both, as I discuss in Part III on the economic organization of the post-PWLO world, is technology. But cultural evolution is far slower and, as I noted earlier, socio-political myths can be to be obstacles to cohesion as well as adhesives. How both the West and the dragons exploit cultural commonalities and fissures between nations and peoples will play a crucial role in determining both the final days of the PWLO and the shape of its successor.

The new wars of religion & the blind evangelists

Consider the myths of international order embedded in recent speeches by the presidents of the world’s three leading powers (with my emphasis added):

“We should foster a new type of international relations featuring win-win cooperation; and we should forge partnerships of dialogue with no confrontation and of friendship rather than alliance. All countries should respect each other's sovereignty, dignity and territorial integrity, each other's development paths and social systems, and each other's core interests and major concerns.”

— President Xi Jinping, Opening Address to the 1st Belt and Road Forum48

“[The Belt and Road Initiative is] a truly important and global idea that is spearheaded into the future, towards creating a fairer multipolar world and system of relations. Russia and China…share the striving for equal and mutually beneficial cooperation towards universal, sustainable and lasting economic progress and social welfare based on respect for the civilisational diversity and the right of every state to its own development model.”

— President Vladimir Putin, Keynote Address to the 3rd Belt and Road Forum49

“America is back. Diplomacy is back at the center of our foreign policy…global challenges — from the pandemic to the climate crisis to nuclear proliferation — …will only to be solved by nations working together and in common. We can’t do it alone…we must start with diplomacy rooted in America’s most cherished democratic values: defending freedom, championing opportunity, upholding universal rights, respecting the rule of law, and treating every person with dignity. That’s the grounding wire of our global policy — our global power. That’s our inexhaustible source of strength. That’s America’s abiding advantage.”

— President Joseph R. Biden, on “America’s Place in the World”, 202150

All three visions for global order appeal to cooperation to solve common global problems for the benefit of all. But Presidents Xi and Putin both call for a “new” global order in which the words “equal”, “universal”, “diversity”, and “dignity” are explicitly reserved for sovereign states. Nowhere in either of their speeches can one find the word “value” and only Mr. Putin, once, as quoted and referring to states, mentions “rights.” In contrast, the focus of President Biden’s first foreign policy speech on taking office was a return to the old order: “America is back.” The vision he expresses for international relations is entirely grounded in “values” and “rights” while “dignity” is for the individual, not the state. Even the common global problems they want to solve are different: Messrs. Xi and Putin enumerate economic progress, social welfare and territorial integrity (without irony), while Mr. Biden focuses on climate and nuclear proliferation.51

The difference is quite stark, even if subtle, and defines the battle lines for the next phase of Global entropy. The dragons explicitly recognize that socio-political myths, or culture, define nations and are not necessarily common across them, hence, can be obstacles to international relations. Consequently, Messrs. Xi and Putin focus their diplomacy on those state-to-state interests that truly are universal — state security and economic welfare — where they have an advantageous position on a hill above the cultural battle ground.

British historian Tom Holland contends that Western secularism — its scientific progressivism, rights-of-man enlightenment and broader values — not only reflects but is a god-less extension of the European Christian culture from which it arose.52 Mr. Holland goes even further by defining a culture war as a battle of “sublimated theology” regarding “the limits of religious authority over a secularizing state” but that “one side doesn’t recognize [it’s a debate over theological] and the one side does.”53 By analogy, the battleground chosen by the dragons is over the limits of a secular international order over religious states, or states whose cultural values may conflict with either Western secularism or its Christian roots. Further, one side doesn’t appear to recognize the centrality of religion or culture to the fight.

Seen in that context, President Biden’s vision as stated above — in words that eerily echo those of the late Madeleine Albright quoted earlier — appears to describe American diplomacy in almost evangelical terms. Worse still, he appears blind to the terrain on which the dragons have pitched for battle: the real choice other countries face is not between the economic might or military power of each side, but over the national sovereignty of cultural values. Presidents Xi and Putin make clear that nations choosing BRI can keep their own socio-political myths. But even as Global entropy erodes its cachet, the leader of the West is pushing for hike in PWLO membership dues: full adoption of Western values.

President Biden is not an outlier among either American or Western leaders. Not to be outdone by Americans in evangelism, the EU describes its own policies on human rights thusly (my emphasis added): “The European Union's policy is based on internationally agreed frameworks and standards, reflecting the belief that human rights and democracy are not ‘Western’ values but universal values to which all UN members subscribe.”54 This rhetoric is common across Western nations and is tied to a lengthening list of “universal human rights” enforcements on aid and official lending.55 Indeed, the Lisbon Treaty enshrined in the EU constitution a legal requirement for human rights promotion in all external EU activity.56 Even the World Bank despite noting that “[u]nlike other agencies which have explicit human rights mandates, our role within the United Nations system does not assign to us a human rights mandate,”57 suspended loans to Uganda over its anti-homosexuality law as it “contradicts the World Bank Group’s values.”58

The problem for the West — and global stability as it stands on a precipice — is that non-Western peoples, contrary to the EU’s belief, do not seem to hold their values.

Trigger warning

At this juncture I need to issue a trigger warning. Below I discuss and present evidence for the above contention the that the values the West promotes — and indeed is relying upon to bind together the PWLO — are not shared by most people beyond its borders. In fact, it would be more accurate to describe Western values as an outlier, in the sense that many other countries’ values — even those of rival religions and political ideologies — are closer to each other than to the West. A key element of my thesis, that we stand on a precipice, one step away from a Complexity cascade that would bring about the swift and final end of the PWLO, is that most Westerners — not just President Biden — are blind to the values bubble of their own creation.

One result of that bubble and the blinders that (often) accompany it is that some of the ideas I describe below may appear so foreign that they shock or even offend. This is especially true of an issue that is one of the most highly charged of flashpoints between the West and many developing countries right now: sexual rights. For most of us in the West, myself included, sexual orientation is now clearly accepted as a human right. But as I demonstrate below, outside of the West, most other cultures view sexual and reproductive choices not as individual rights but as societal choices based on collective cultural values.

Two examples from the survey data I use in my analyses clearly illustrate the chasm between the West and others on the issues of sexual rights versus cultural values. The World Values Survey is a detailed set of over 94,000 personal interviews across 64 different countries.59 Among the survey questions are two that ask respondents to rate on a 0-9 scale the acceptability of “homosexuality” and “sex before marriage”. In Western countries, the average of within-country share of respondents who report that “homosexuality” is “never acceptable” (0 on the 0-9 scale) is 10.6%, while 6.6% feel the same about premarital sex. In sharp contrast, among non-Western countries, the average within-country share of respondents who believe homosexuality is never acceptable is 47.2%, while 36.8% say the same of fornication. In roughly two-thirds of non-Western countries, the share of respondents for whom both sexual activities are “never acceptable” is triple that of Western countries. This staggering difference stems from the equally great wide chasm in world views: in the West both choices are seen as individual rights, while in most other countries they are defined as cultural values. As difficult as it may be to accept, the West is truly an outlier where sexual rights are concerned.

The Western outlier

Like Tom Holland, Joseph Henrich, an evolutionary biologist at Harvard University, also sees the West as distinctly different from other cultures and similarly roots that difference in the early Christian church.60 He describes the West as WEIRD: Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. Dr. Henrich’s work is based on large-scale, cross-cultural comparative experiments on psychological and behavioral variables, not values per se. He also notes a psychological characteristic of Westerners that well accords with my contention that the West is blind to its own differences: a tendency to seek and see universal truths where none exist. But a comparison of values rather than psychology reveals that the West is not just weird, it is a mathematical outlier.

Figure 1 from the World Values Survey (WVS) provides a visual representation of how different Western values are from the rest of the world. The Inglehart-Welzel World Cultural Map reduces the 259-question WVS of social attitudes and cultural values into two dimensions of “traditional versus secular values” and “survival versus self-expression” (defined by the Inglehart and Welzel).61 Inglehart & Welzel’s original color overlay helps illustrate broad cultural groupings, but deceivingly also gives the impression cultural continuity is greater than it is.

The reality of Western-values weirdness is better seen in the density and spacing of the 107 individual country dots across the “map”. The majority, which I have annotated with a green-dash circle, 81 in total with a few stragglers just beyond its borders, crowd around the (0,0) point on the graph. A sparsely populated zone with another 9 dots runs roughly “North-South” to the “East” of the main group, from Uruguay to Japan (annotated with a grey-dash box). But the core of Western countries (annotated with an orange-dash oval) are tightly grouped, ironically, in the “Far East” of map. There is an interesting — and noteworthy — exception: the US, nestled with Belgium and Luxembourg in the intermediate zone. Its cultural position on the map may help explain why culture wars among Western nations appear most intense in the US.

The visually apparent cultural distance of the West from other countries can be formalized and quantified. Using the most recent WVS data set (Wave 7, based on 94,278 interviews in 64 countries over 2017-2022), I mathematically calculated the cultural distance of each country from the Western “center,” both overall, based on answers to all 259 questions, and for 13 subgroupings of questions. I defined the Western center as the (demographically weighted) average response across questions from the seven Western countries in Wave 7 (Australia, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the UK, and the US). Distance from the Western center was defined as the within-country, across-questions average of absolute differences in individual responses from the Western center.

Figure 2, for the 64 countries in Wave 7, paints the globe with the overall (259-question) distance from the Western center. As in the Inglehart-Welzel map, the West is visibly different (lighter) than the rest of the countries in the survey. Also in keeping with the Inglehart-Welzel map, the US is not quite as “Western” as the other Western countries in the survey.

While the WVS has its own subgroupings, both they and many of the questions in the survey betray significant Western-values bias.62 As a result, I constructed my own subgroups. From among the 259 questions in the WVS, I selected subsets of questions (listed in the Appendix) that addresses three broad subcategories — Personal values, “ESG” values, and Basic needs — and further divided those into ten subindices within them. The final subcategory, Basic needs, relates less to cultural values than economic welfare, but there is an obvious tradeoff for some countries. The ten subindices are listed as axes of a “spider graph” in Figure 3 with regions of the graph shaded in correspondence to the broader value subcategories. Plotted across the 10 axes are “webs” illustrating the distance of various regional/cultural groups from the Western center in each cultural values subindex.

There are two notable features of Figure 3. Most obvious and consistent with the previous charts, is how distant all other regional/cultural groups are from the West in every dimension. African and Islamic countries appear to be in a wholly different orbits. But even the values of other European countries, though closer, sit well outside of the subset I have defined as above as the West. The next obvious feature is its imbalance: the far greater salience of the first major category, Personal values, in defining differences with the West. By a significant margin, the greatest differences from Western values for each region are in: (i) the importance of family over the individual, (ii) women’s place in the home and society, (iii) sexual behavior, and (iv) god and religion. Only in Africa and Latin America, and only for survival (food, shelter and minimum income), are distances from the West greater than some of the subindices of Personal values.

How many divisions has the Pope?

According to legend, at the Tehran conference in late 1943, Joseph Stalin responded to Winston Churchill’s suggestion that the Pope may be influential in the war against the Nazis with “The Pope. How many divisions has he?”63 As you ponder a 20-month long war of attrition in Ukraine and the rapid and uncertain escalation of the Hamas-Israel war, you may be asking a similar question: do differences in cultural values really have any relevance to the dualist struggle between the US and the dragons for defining the world order? I submit that not only are they relevant, but they will play a crucial role in shaping both to the future path of Global entropy and the world order emerges from it.

As noted previously, socio-political myths/cultural values are weak adhesives at the level of international relations, but they are extremely potent weapons as millennia of religious and inter-cultural strife attest. Like combined arms maneuver in combat,64 military and economic power are far more effective when combined with diplomacy and information operations designed to exploit cultural differences. President Xi and Putin’s respective vision statements above clearly incorporate exploitation of cultural divisions as part of a “combined arms” grand strategy in their “unrestricted warfare” on the PWLO. They are likely to be aided in their efforts by other would-be regional powers like Iran and potentially Turkey65 that view the PWLO as an impediment to their own aspirations in a new world order.

Weaponization of cultural differences likely would play a leading role in generating a Complexity cascade that accelerates both the speed and resulting disorder of Global entropy as it spreads to other regional powers that at present derive benefit from the PWLO. The PWLO enhances the security of India, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, and Japan vis-à-vis the dragons and their allies with whom each has an historic rivalry. But as the PWLO weakens, and with it their perceptions of the PWLO’s protections, self preservation may shift their incentives. Because these powers are key planks to the PWLO and sometime regional rivals themselves, the dragons and their allies will have an incentive to exploit any cultural gaps between them and the West or each other.

Finally, an understanding cultural distances is necessary to forecast what will follow the PWLO. Regardless of the speed of Global entropy — whether it is the disorderly collapse I fear, or it lingers on powerlessly like the Holy Roman Empire — the order that emerges from its aftermath will require its own socio-political myth(s) to bind it. That process will require finding common cultural ties and will be made harder by weaponization of cultural differences during Global entropy.

Accidental guerrillas

As noted above, Western blindness to its own cultural weirdness is ceding favorable terrain on the battlefield to its adversaries. Worse, contrary to President Biden’s characterization of Western cultural values as an “abiding advantage,” the West’s increasing tendency to link acceptance of Western cultural norms to PWLO membership is more likely a major strategic blunder. The titular protagonists of another of David Kilcullen’s books, The Accidental Guerrilla, are neutral or even friendly populations that are turned towards insurgency by the actions and behaviours of a counterinsurgency force.66 By analogy, by enforcing adherence to Western values that may run counter to their own as a condition of membership in the PWLO, the West may be making “accidental guerrillas” of countries and driving into the arms of the dragons.

An explosive example

This is not just speculation on my part: it appears to be happening in one of the most strategic global battlegrounds, Africa,67 in a conflict over fundamentally different views of sexual orientation. The issue is inflaming relations with the West across the continent, but Uganda, where a recent law makes “aggravated homosexuality” punishable by death, has become a flashpoint in the conflict. As noted in my trigger warning, the West views homosexuality as a human right, while most Africans see it in terms of cultural values. These radically different perspectives — and the West’s blindness to the difference — are plainly apparent in the difference of the Western press’s coverage of the conflict from the African press.

In articles earlier this year on Uganda’s law, both the British Broadcasting Company68 and the American Associated Press69 frame the conflict in terms of individuals’ universal human rights, defining it in the language of Western leaders and the UN human rights office. Demonstrating Western blindness to the potential for cultural differences to drive the conflict, both articles blame the newly passed Ugandan law and others like it across Africa on legacy colonial laws. As if to emphasize that blindness, the AP reporters immediately follow their assertion by noting that Archbishop Stephen Kaziimba, head of the Ugandan Anglican church, has split with the Church of England on the issue and worked closely with the government to enact the new law.

For a shockingly different perspective consider an Op-Ed in Nigeria’s second largest newspaper, The Guardian on conflict with Western nations over issues of sexual orientation.70 Though potentially jarring, it is worth a read for anyone unfamiliar with traditional cultures’ perspectives on these issues.71 The Op-Ed is well researched, highly legalistic and focused on the rule of law, national sovereignty and the importance of national identity. Citing juris precedent from the European Court of Human Rights, the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights, and sovereign laws throughout Africa, and noting that “[t]he rule of law is a critical factor in empowering individuals, improving human flourishing, and preserving peace in a country”, the Op-Ed flatly states that “Same-sex gay marriage…[and] LGBTQ1+ are not human rights…There is no known international law that obliges Nigeria and other African countries to legalise gay marriage and LGBTQ1+.”

Illustrating clearly the powerful wedge these issues create for the dragons to fracture the PWLO, the authors assert that “LGBTQ1+ goes against our culture, tradition, and beliefs” and advocate that “Nigeria should hold tenaciously to this position notwithstanding the threats or sanctions brandished by the West.” Citing UN law that “every developing country…must reflect the diverse social, economic, and environmental conditions of the continent with full respect for their religious, cultural backgrounds, and philosophical convictions” the Op-Ed decries that “subscription to LGBTQ1+ aberration” now is a precondition for World Bank loans and academic research grants, the EU’s pressure to include a mandate to legalize LGBTQ1+, abortion and transgenderism in the EU-Africa-Caribbean and Pacific trade agreement, and that “U.S. President Joe Biden has made LGBTQ1+ the centerpiece of American foreign policy.” The article closes by noting that “Nigeria is a sovereign country with the right to decide for herself the kinds of laws to enact for her own good…A people without identity are a people without existence…[Nigeria] must remain [true to its identity] in the interest of the country’s democracy, foundational philosophical and legal principles.”

The issue of sovereignty is also key to the African perspective in a more balanced article in the Ugandan Monitor that acknowledges the Western human rights perspective, but also plainly identifies Western economic coercion — restricting development loans, aid and foreign direct investment — as interference in the sovereign choices of a democratic nation.72 The Monitor article quotes Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, “Uganda will only happily work with all the countries that respect its sovereignty.” And, these are not minority views in Africa as protests and political activity from Ghana to Kenya to Mozambique to South Africa attest.73

It is not an accident that the words chosen by Presidents Xi and Putin in their respective pitches for an alternative world order closely jibe with those of The Guardian Op-Ed writers and President Yoweri Museveni. Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi, on a tour of Uganda, Kenya and Zimbabwe earlier this year — the first visit to Africa by an Iranian leader in 11 years — was even more pointed, focusing much of his rhetoric on Western pressure over sexual rights and its disrespect for national sovereignty: “The Western countries try to identify homosexuality as an index of civilization”; “by promoting homosexuality they are trying to end the generation of human beings”; “acting against inheritance and culture of nations”; and are “not generally interested to see countries who enjoy great resources and national reserves to be independent.”74 Demonstrating that Iran is no less proficient at “combined arms” diplomacy, President Raisi offered financial support for an oil refinery and pipeline in Uganda that is opposed by European nations and signed five memoranda of understanding with President William Ruto of Kenya.

With strings attached (to repel rather than bind)

There is compelling evidence that the wedge created by these issues is having measurable realignment effects and hastening Global entropy. A recent academic paper by researchers at the University of Bern finds, seemingly counterintuitively, that Chinese bilateral aid and assistance are more influential with democracies than autocracies in aligning nations’ UN votes with China.75 Yet their results are straightforward in the context of the example given above and the respective choices autocratic and democratic leaders face when international relations are fought on a battleground of cultural values.

In autocracies, leaders do not need to seek popular support to enact laws, nor do they need to enforce them if they know their populations are opposed. In contrast, as explicitly noted in The Guardian Op-Ed above, the rule of law is a fundamental principle of democracy and representative governments must reflect the will of their voters or face removal. Western powers are presenting a no-win choice to elected representatives in democracies with values that fundamentally collide with the West: be voted out of office for enacting laws their populations strongly oppose, or lose access to Western support. When China, Russia and even Iran are offering support without values-strings attached, the choice becomes easy.

To test this thesis, I ran a couple of simple cross-sectional regressions on determinants of countries’ US votes in favor of Ukraine/opposing Russia in its invasion, including its 2014 annexation of Crimea.76 Taking advantage of the same extensive database on Chinese official and unofficial aid as the researchers in the University of Bern study (AidData),77 I focused my analysis on China’s potential influence on UN votes. That the votes relates to the actions of Russia — which China supports — rather than to China itself makes the results even more powerful.

In the first model I included each country’s total exports to and imports from China, both as shares of GDP, to measure the effects of and control for the depth of economic relationship. To assess the influence of Chinese financial aid I included the annual average of total aid received from China (official development, military and Huawei assistance), again as a share of recipient-country GDP. Finally, to measure the independent effect of cultural values, I included the the country’s cultural-values distance from the Western center (average), as described earlier. The top panel of Figure 4 displays the results. Neither trade variable has a statistically significant effect on UN votes (both p-values, the probability that is no relationship, are greater than 0.85). But, consistent with the previously cited study, aid from China does have a statistically significant negative effect on countries UN votes in favor of Ukraine (with the statistical probability of zero relationship just 1.3%).

Yet, even after controlling for economic relationships and all forms of Chinese aid, a country’s cultural distance from the West also has a negative effect on votes for Ukraine that is of the same degree of statistical significance as aid. Staggeringly, putting the coefficients in comparable terms, Model 1 suggests that a cultural distance from the West roughly equivalent to the average distance of other European countries from the West in the spider diagram of Figure 3 is worth 6.8% of recipient-country GDP in annual assistance.78 Given that many African and Islamic countries are more than four times that distance, Model 1 suggests that enforcing adoption of Western values is equivalent to paying whole nations — or perhaps even a whole continent — 25% of GDP per year to study human rights law.

Model 2 in the lower panel of Figure 4 omits the trade variables and focuses on different types of aid: development aid, military aid, and infrastructure aid from Huawei, a Chinese telecommunications technology company at the forefront of 5G networks. Interestingly, when Chinese aid is broken into component parts, none of them are as statistically significant as they are in sum, though Huawei aid (the smallest component by far for most recipient countries) appears the most statistically significant in aligning countries with China. Given the high degree of correlation between the three types of aid, however, that implication is less clear.79 But both the magnitude and the statistical significance of cultural-values distance are undiminished.

Global entropy is inevitable, but adaptation may slow it

The clear implication is that cultural values do matter for international relations, but for many countries they have the opposite effect to President Biden’s intent when he refers to them as “America’s abiding advantage”. For policymakers, the lesson here is that coupling Western values acceptance with aid comes at a cost, an extremely high cost if coefficients of Model 1 are to be believed. The question then becomes whether it is worth that cost.

All of international relations represents tradeoffs. A variety of studies show that conditionality in development lending can be more counterproductive than helpful in achieving its stated aims, particularly human rights.80 Other research questions even the moral foundations of coercive aid, noting its unavoidable tension with rights of self determination, which undermines the socio-political myths undergirding PWLO international institutions.81 If Apex neoliberalism’s moral interventionism is ineffective, of questionable moral validity despite the goodness of its intent, and risks dissolution of the international architecture with attendant consequences that include increased potential for warfare, it is fair to ask whether it should be abandoned in favor of an alternative.

There are voices for change. Amrita Narlikar, president of the German Institute for Global and Area Studies in Hamburg points to two opposing narratives for the problems of the PWLO.82 The first, “Resuscitate and Reinforce” argues that the problem is abuse of it by individual members and that its institutions need to be strengthened to contain them. Without irony, advocates of this view generally cite former US President Trump’s turn to isolationism and “America first” policies as examples of member-state abuse of PWLO institutions.83

The second narrative, “Restructure”, instead believes the PWLO needs fundamental restructuring and views home-country-first policies as a bedrock of honest multilateralism that better reflects state sovereignty. Dr. Narlikar notes that one variant of the Restructure narrative, notably espoused by NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg, focuses on building alliances of common values rather than pushing common values on those that do not hold them.

There are historical precedents for an American foreign policy that includes morality but applies it more flexibly. A key foreign policy debate in the 1980 US election was between the moral absolutism of President Jimmy Carter and the flexible realism of President Ronald Reagan. Mr. Reagan won the election and over his succeeding two terms in office, despite supporting dictatorships that partnered with the US against the Soviet Union, oversaw the transition of several of them in Latin American and Asian to democracy through persistent soft diplomacy in the background.84

Given Global entropy’s advancement past the likely point of no return and the potential for culture to act as both repellant and adhesive in international relations, Western adoption of this variant of the Restructure narrative likely will play a determinative role both in what global order succeeds the PWLO and whether that path is disorderly or evolutionary. For markets, the lessons of the above analysis are even clearer than for policymakers: if Western powers fail to adapt and continue to fight on the battleground chosen by the dragons and their allies, Global entropy likely will accelerate and risks a disorderly descent into a Complexity cascade with attendant increase in geopolitical, economic and market Uncertainty.

Battlefield topography and axes advantages

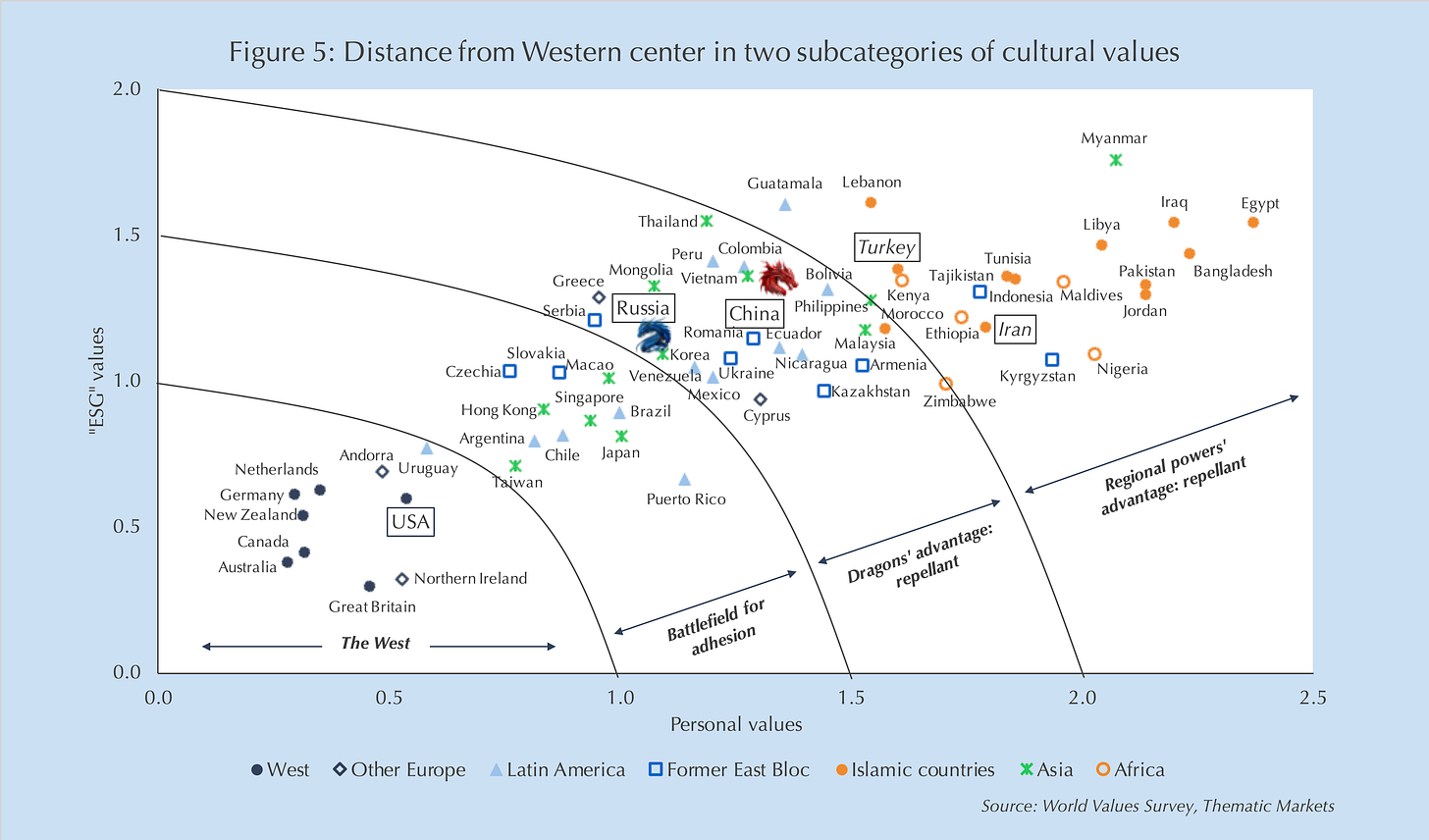

To assess both how quickly Global entropy may proceed, where its points of fracture lie, and ultimately what order may emerge from it, a careful examination of the field of battle is useful. Figure 5 presents the cultural distance from the Western centre of the 64 countries in Wave 7 of the WVS along two cultural-values subcategories introduced earlier: Personal values (family, the role of women, sexuality, and religion) and quasi-ESG values (individual freedom, tolerance and the environment). Countries are color-coded by their regions as defined earlier in Figure 3. Even more so than Figure 3, it highlights how “weird” the West is relative to the world. It also makes clear that the West may be smaller than it thinks of itself considering the distance of countries like Czechia, Greece, South Korea and even Japan.

Isoquants of distance (semi-circular lines in Figure 5) show Western cultural values’ figurative “fires range” on the cultural battlefield. The isoquants are spaced at roughly the unit of distance shown in Model 1 to be worth development aid equal to ~6.3% of recipient-country national income.85 While the West may be smaller than it defines itself, the innermost pair of isoquants suggest the nations that are the battlefield for cultural adhesion; i.e. those countries that are more likely to share sufficient values with the West to form stable alliances in a new world order. Countries beyond that range are instead more likely to be repelled by Western cultural values than attracted and thus are susceptible to the dragons’ cultural warfare. Countries beyond the last isoquant are so distant from the West that, as tensions over sexual rights in Africa attest, pushing Western values are highly likely to push them into the dragons’ arms. That includes two would-be regional powers, Iran and Turkey, that may have an advantage in plying countries away from both the PWLO (as Iran clearly is attempting in Africa) and the dragons.

But the relative positions of both the dragons and would-be regional powers to other countries is deceiving. Figure 5 measures cultural distance from the West only, not one country versus another. By analogy, both Chicago and Karachi are roughly equidistant from London, but are nearly twice that distance from each other. Thus, while Korea appears to be “next to” Russia on Figure 5, its overall cultural distance from Russia is nearly as great as Uruguay from the Western center.

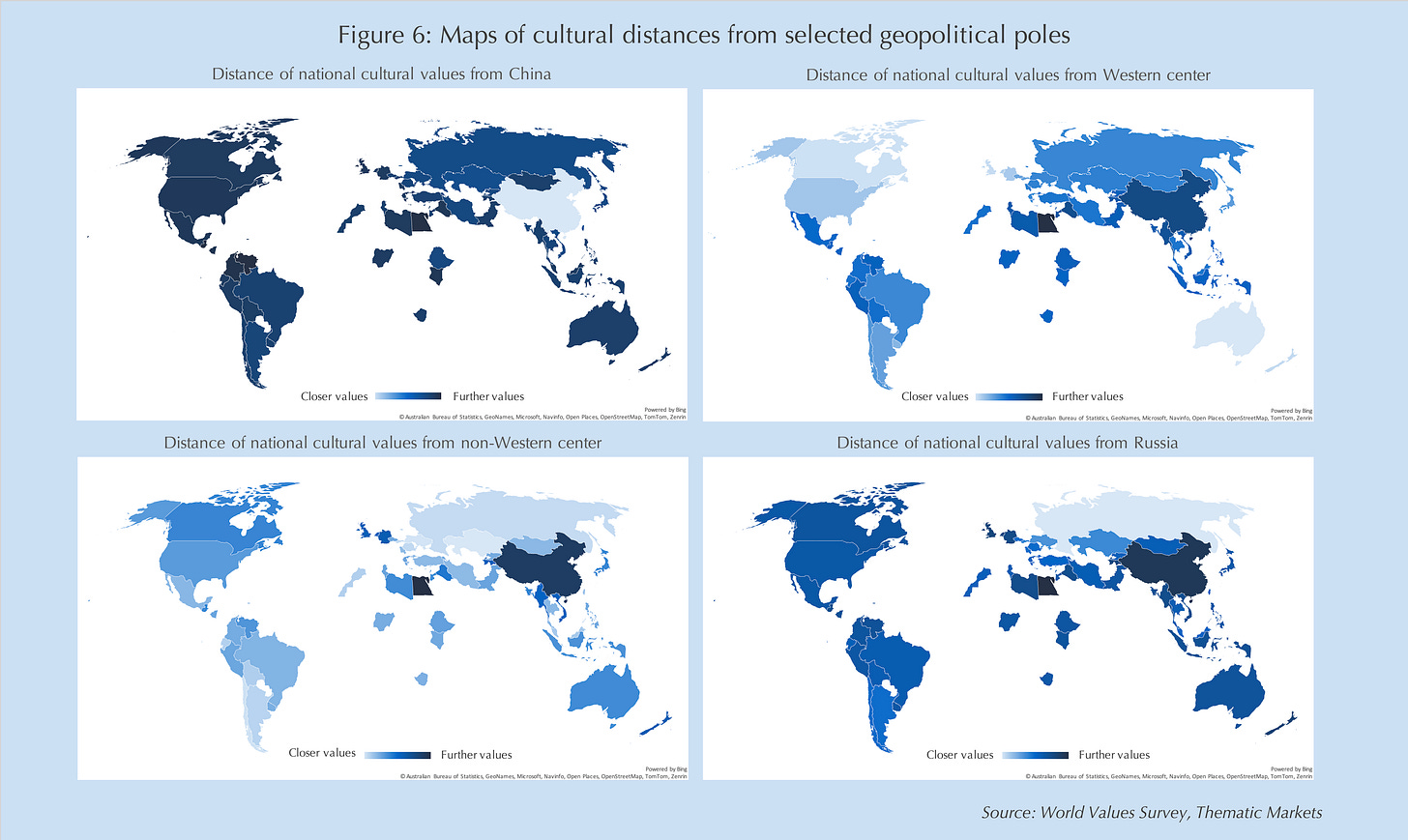

Figure 6 repeats the cultural values distance map of Figure 2 (upper right) for comparison with China (upper left), Russia (lower right), and “Others” (lower left), defined as the center (average) of non-Western countries’ cultural values.86 As culturally weird as the West is from the rest of the world, the dark shading of nearly the whole globe in the upper left of Figure 2 shows that China is practically an alien. This should be taken with a grain of salt given that all surveys in China are monitored by the CCP and many of the WVS survey questions were omitted in China. But it seems fair to say that while cultural values may be an effective weapon of repellant for China in fracturing the PWLO, they may not be useful in returning China to its desired role as the “Middle Kingdom”.

While not easily apparent with Microsoft’s color scaling, the cultural distance from Russia of most countries (other than China and Egypt) is roughly narrower than for the West, suggesting that it may have an easier time than China using culture as an adhesive to build alliances in the post-PWLO order. The “Other” map is a bit difficult to interpret as it isn’t the cultural values of any specific nation or group of nations with shared cultural heritage like the West, but rather the average of all the other countries. But in lieu of doing this analysis for every possible regional power, it serves as a useful proxy of regional powers’ cultural affinity. The shading of the Other quadrant map, as one might expect from its definition, is both lighter (culturally closer) overall and more varied than the other quadrants, indicating that there is significant room for regional powers to form culture-based alliances to compete with the great powers.

Although daunting at first glance, Figure 7 provides a more detailed and analytically useful representation of Figure 6. Each of the four quadrants plots the overall cultural distance of countries from two different geopolitical poles: West versus China in the upper right; West versus Russia in the lower right, Russia versus Others in the lower left, and finally, China versus Others in the upper left. Countries’ relative distances are shown by the markers in each quadrant that are color-coded for region (with China and Russia illustrated by dragons of course). The 45º lines in each quadrant represent where countries are equidistant, culturally, from the two poles, hence each quadrant can be divided into two “triangles of cultural advantage.” For instance, country markers falling in the two green triangles are closer to the West than to China (upper-right quadrant) or Russia (lower-right quadrant).

Keeping in mind that earlier caveat regarding the possible problems with the WVS in China, Figure 7 makes even more clear China’s problem in building alliances based on culture. The only country culturally closer to China than the West is Egypt, the far-outlier orange dot in each quadrant. In the upper-left quadrant, no country is remotely closer to China that the Other center. This suggests that in any new world order, China’s route to dominance will be purely based on military and economic power. That doesn’t make it impossible, but international relations built solely on power are more difficult achieve and far less stable. China’s “culture problem” reinforces the notion that is partnership with Russia, a European Orthodox country with few cultural similarities, is based on complementarity in powers and the repulsion of both from the West.

Russia is in a much better position vis-à-vis the West. Only two non-European countries, Uruguay and Japan, are culturally closer to the West than Russia (the other Latin American marker in the Western triangle is Puerto Rico, a US Territory). This gives Russia an advantage within its duo-pole with China, given the latter’s apparent culture problem. The allies of the Sino-Russian duo-pole in a new world order are much more likely to side with Russia culturally, potentially posing a problem for the stability of their duo-pole, especially if the West weakened significantly, lessening the repulsion pushing them together.

Turning to the left half of Figure 7, the strength of regional powers becomes apparent. Admittedly, it is partially by construction, but the Others center is culturally closer to every country than either China or Russia, with the exception of Czechia and Ukraine that are marginally closer to Russia. Furthermore, keeping in mind that distances between markers do not necessarily indicate cultural closeness of countries, the placement of would-be regional powers Iran and Turkey in all four quadrants — in the middle of the pack and closer to Islamic and African countries — does suggest that they each have cultural advantages in finding regional alliances.

Endgame: Postulating a new world order

Culture alone will not determine the shape of the new world order that emerges from Global entropy. A stable world order will need to be underpinned by economic might and military power. But cultural differences likely will play a determinative role in how Global entropy progresses from here, and in particular, how rapidly it advances. The speed of entropy will, in turn, have a large effect on economic and military power dynamics, and in a disorderly descent, the role of cultural differences may be as great or greater than wealth and power in determining the outcome. As a result, even though culture is likely to play second fiddle to economic and martial factors in orchestration of the new world order, it likely will write the score.

An evolutionary path to global bifurcation

Global entropy already has been underway for more than two decades, and despite bumps along the way and a significant step-up in Uncertainty from historically low levels, the path generally has been smooth to date. Even the current global disorder, with a major war in Europe, a smaller one in the Middle East, and ongoing threats in Asia is relatively peaceful in comparison with much of recorded history. The most likely path forward is one of steady evolution towards a new equilibrium in international affairs. In a world where Global entropy proceeds slowly, fundamental forces determining wealth and power are likely to generate a bipolar world with lesser regional powers playing a role.

As I will cover in greater detail in Part 3, the geostrategic implications of Global entropy, acceleration of increasingly specialized technological advancement, and path dependence are pushing the global economy and military power towards bifurcation. Technological progress is driving both an increasing share of economic value creation and military advantage. As a result, and as we already see in rapidly multiplying controls on technology exports and information, leadership in technology and associated mechanisms of control will be the new currency of economic and military power. Two centers of technological excellence — the Anglo-sphere and China — are rapidly outpacing all others. The proliferation of controls, rising Localization of production, and the increasing influence of path dependence generated by the concentration of leading universities, research institutes and learning-by-doing in these two centers of excellence likely will reinforce their dominance.

The bipolar ascendancy also will be reinforced by economic network effects. As Localization replaces outsourced global supply chains, particularly within the technology bipoles, the nature of “economic coercion networks” will change.87 The interdependence of suppliers and procurers in the globalized system likely will yield to greater coercive power of technology leaders, via export controls, over increasingly supplicant trading partners. That process would further consolidate and entrench network externalities that stabilize the bipolar system.

But one group of exporters likely will retain power over the technology originators in the new economic order: producers of essential natural resources, especially those needed for advanced technologies (critical minerals) and the functioning of economic activities (energy). The uneven geographic distribution of these resources dictates that power and has important implications for the form of bipolarity, geopolitical alignments and space for regional powers that likely will manifest.

While the Anglo-sphere is well resourced — the US, Canada and Australia lack few if any natural resources — China would be dependent on external sources: Russia, Africa and Latin America. Supply from the latter two would leave China dependent on open sea lanes (and alliances) in a world of distributed, autonomous weapons with long-range fires capability. This vulnerability and Russia’s need to access advanced Chinese manufactures likely will reinforce their strategic coupling as a duo-pole. Investment in hardened over-land transportation networks likely will further cement the relationship, as will the cultural repulsion force of a strong geopolitical rivalry with the Western pole.

The strategic rivalries between the bipoles likely would still result in intense competition for resources that leads to a more fluid system of international relations than the current PWLO with space for the growth of lesser regional powers. Cultural affinity and mutual security should continue to bind Western Europe to the Anglo-sphere pole, while cultural rivalry (with China) and mutual security should keep Japan, India, and South Korea within the alliance. Similarly, North Korea and most former Soviet states likely will be bound to the Sino-Russian pole by cultural repulsion and trade dependencies. But these allies will require their own secure resource supplies, pushing both poles into competition to secure the resources of Africa and South America. Distance, proliferation of cheap but increasingly sophisticated and accurate weapons, and resource constraints on both poles likely will allow for greater fluidity in international relations outside the tighter alliance networks.

Regional power aspirants Iran and Turkey can be expected to step into that breach to build independent regional power bases that play the bipoles off each other. Both can draw upon broad cultural networks (Islam and Turkic speakers), closer cultural distance to other traditional cultures, and their burgeoning (albeit lesser) leadership in affordable military technologies to tap into the more fluid landscape of international relations. With the exception of Saudi Arabia, who likely will be driven towards alliance with the West by Iran’s alienation from it, there are few other potential regional powers with the combination of aspiration, resources, political cohesion, economic stability, and technological sophistication to emerge as regional powers in the predominantly bipolar evolved order.

An evolutionary path of Global entropy to a new world order still faces significant Uncertainty and likelihood of strife. But it likely will allow for more rapid global growth that should strengthen the Western pole in relative terms as the Eastern pole, particularly China, faces greater demographic decline, less internal dynamism and more significant internal economic challenges, including overcoming the “middle-income trap.”88

Rapid descent to anarchy

In contrast, a rapid pace of Global entropy is far more likely to result in disruptive effects on economic networks, weakening the power of technological leadership to coalesce into two firm bipoles, and lead to a more fractured global order, or even the absence of a stable order for an extended horizon.

A rapid unwind of Global entropy likely would arise from self-reinforcing extended conflict between global powers and regional powers that encompasses the full range of warfare: economic, informational, cyber, and kinetic. Despite their technological advantages, the West and China — both overly indebted already — would be severely drained by the experience, straining their economic and military capabilities, and ability to lead or even form alliances. Global economic growth would be depressed by disorder, the possible end of safe, reliable sea lanes for trade, and extensive fracturing of the global political and economic system. Even Localization of production likely will be slower amid the higher debt and Uncertainty that result. Accordingly, the evolution of bipolar technical and economic domination from path dependence and network effects likely would be slowed or perhaps even stalled.

Both the West, with its prestige damaged, perhaps irreparably, by the rapid collapse of the PWLO, and an economically and militarily stretched China that is culturally distant from everyone likely would struggle to form alliances as the radius and credibility of their respective security umbrellas receded. A weaker Western alliance would, in turn, weaken the Sino-Russian relationship as Western repulsion became less meaningful, while China’s demographic decline and economic malaise, and Russia’s greater advantages in forming relationships of cultural affinity would reduce the its incentives to couple with China.

The diminution or even disappearance of bipoles would create a vacuum that draws in a wider collection of regional powers. Russia, India, Japan, Saudi Arabia, and perhaps even Indonesia and Poland likely would join Iran and Turkey in the ranks of regional powers. A weakened Anglo-sphere and Western Europe likely would remain in cultural alliance, but be less able to project power in an increasingly fractured world. Without strong bipoles to suppress them, jockeying regional powers likely would further exploit and be driven to conflict by cultural differences. Turkey and Iran in particular may come into conflict with Russia and China over Turkic-speaking, muslim peoples the former Soviet states and China’s Xinjiang, or could be drawn into potential sectarian conflicts between India and its muslim neighbors or Indonesia and its non-muslim neighbors.

Regional power conflicts likely would spill over into proxy wars in both Africa and Latin America, where, at present, no states appear politically and economically strong enough to become independent regional powers. (Both Brazil and Venezuela have the potential, but suffer from weak internal institutions and political stability, excessive debt, and poor human capital.)

The forces of technological progress and consolidation that likely would drive bifurcation in the world of evolutionary Global entropy also would ultimately lead to more stable international relations in a rapid, chaotic Global entropy. But the process would take longer and, if sufficiently long for the Anglo-sphere and/or China to lose their technological edge, may not result in a bipolar order.

The market and economic implications of the rapid path for Global entropy are a marked rise in Uncertainty from its already elevated levels, slower global growth with potential for a large drop in global trade, and widespread defaults and hyperinflations.

Culture, complex systems and the path to chaos

While the less-chaotic evolutionary path of Global entropy is more likely in my view, as noted before, the world stands on a precipice of a potential rapid descent into a Complexity cascade that would bring about the second, more dystopian scenario. The probability of the latter is uncertain, i.e. both unknowable and non-quantifiable, like the probability of an astroid strike or tsunami. Yet the combination of Global entropy’s advanced stage, the full emergence and roaring of dragons, the West’s apparent blindness to its own danger, and recent developments in international relations, including the newly flared war between Hamas and Israel, all suggest to me that the probability is significantly higher than that of a cataclysmic natural disaster.

Which path we take is a function of complexity, which is why its likelihood, timing and even form is unknowable. Yet, unknowable does not mean that we cannot prepare for it. In Part II, I will address how to insure one’s portfolio against the unknowable, both specific (“known unknowns”) and general (“unknown unknowns”). Important to both, but especially the former, is to understand a Complexity cascade, a Theme I coined during Covid to describe the Uncertainty created by and nonlinear potential of complex systems when they fail.89

How catastrophic collapse happens

All human structures — from book clubs to nations to international orders — are complex systems, meaning they are formed by many independent, usually unpredictable parts. While they often give the illusion of stability, they are inherently non-linear, both internally and in their potential for rapid, unpredictable catastrophic failure. In a masterpiece of brevity and insight, Dr. Richard Cook described in 18 short paragraphs how and why complex systems fail catastrophically.90

Among its insights are that “complex systems are intrinsically hazardous systems” [paragraph 1] that always operate in “degraded” or broken mode [5], i.e. small failures are ever present, like squabbles over which book to read, violent crime or border skirmishes. The mix of failures is constantly changing [4], which is how its internal components — people — learn to repair and stabilize the system [9, 16 & 17]. But Dr. Cook notes that in any complex system, “catastrophe is always just around the corner” [6] and identifies the following key characteristics of catastrophic failures:

A chain of failures that overwhelms the system’s ability to operate in broken mode. [3]

Change that introduces new rare but high-impact forms of failure. [14]

Hindsight-biased safety mechanisms. [7, 8, & 15]

Lack of experience with failure. [18]

Failure to anticipate and adapt to change. [12]