There is an increasing recognition that China’s state-capital model, at scale, is incompatible with Western, market-based economies. Similarly, a broadening political and international consensus is developing that China’s development is a threat to the continuance of the post-War liberal order. What is perhaps less recognized is that China’s industrial policy – based on its national security goals rather than economics – is a drag on global welfare and productivity growth and is itself a geopolitical destabilizer.

While many economists, including the authors of the “China shock” papers detailing the persistent adverse effects of Chinese import growth,1 assume that China’s economic growth has been primarily driven by economic efficiency, a review of its state-capital model, mechanisms of protection and subsidy, and directed investment suggests instead that it has been primarily the result of malign, non-market-based industrial policy. I review the evidence supporting that contention, then demonstrate using industry-level US manufacturing data that China’s industrial policies likely have not only retarded US (and other advanced economies’) productivity growth, but been a drag on global welfare.

My position is not one of advocacy – though I wholeheartedly support barriers to Chinese strategic exports – but of prediction: the trend of bifurcation of the global economy along Western and Russo-Chinese lines now appears unstoppable. At its current size, the Chinese state-capital model is incompatible with open market-oriented economies. Electoral politics in Western democracies demonstrate its political infeasibility, while dangers presented by the asymmetry of its industrial capacity have been laid bare by Covid, the Ukraine war and China’s increasing belligerence with its neighbors. That its model also is undermining global welfare only supports the move toward bifurcation. Preparing for that reality will be necessary for any portfolio managers and business leaders.

I have made this piece freely available to stimulate public policy discourse; the economic and market implications of the unfolding bifurcation are discussed in my paid-only research.

China is not a market economy

Despite having many of the outward trimmings of one, China is not a market economy. While its economy is driven by ostensibly for-profit, joint-stock companies, 68% are to some degree owned by the state2 and all larger firms and joint ventures, private or public, are required by law to have Chinese Communist Party (CCP) cadres within them to align the firm with the interests of the state.3 Indeed, steering China’s industrial might to state purposes is so important to the CCP that experience running a state-owned enterprise (SOE) is a common path to political advancement within the Party.4

But state ownership and CCP alignment are only the first layer of the Chinese industrial policy. China makes use of an elaborate scheme of subsidies, tax incentives, land and research grants, equity swaps, and – most importantly – subsidized directed lending to promote the development of strategically important industries.5 CSIS conservatively estimates that, in total, China spends 1.7 percentage points of GDP per year on industrial policy, more than double the next highest of any other major economy and more than it (officially) spends on its military.6 While it is popularly thought that China’s economic miracle was founded on cheap labor, the reality is that its rapid, strategic industrialization (and technological and military convergence) was built on cheap capital.7 Financial repression of households within a closed capital system channels forced excess savings to China’s big four state-owned banks, whose directed lending at non-market rates is used to build strategic industries.8

The result is that in little more than a quarter century, China has gone from a poor, technologically lagging country with a large but outmoded military to the world’s largest manufacturer – by a wide margin9 – who dominates production in strategically important industries,10 who is the leader in an expanding array of critical technologies,11 and fields not only the world’s largest army, navy, and rocket force, but among the most modern and sophisticated.12

Nor is China efficient or productive

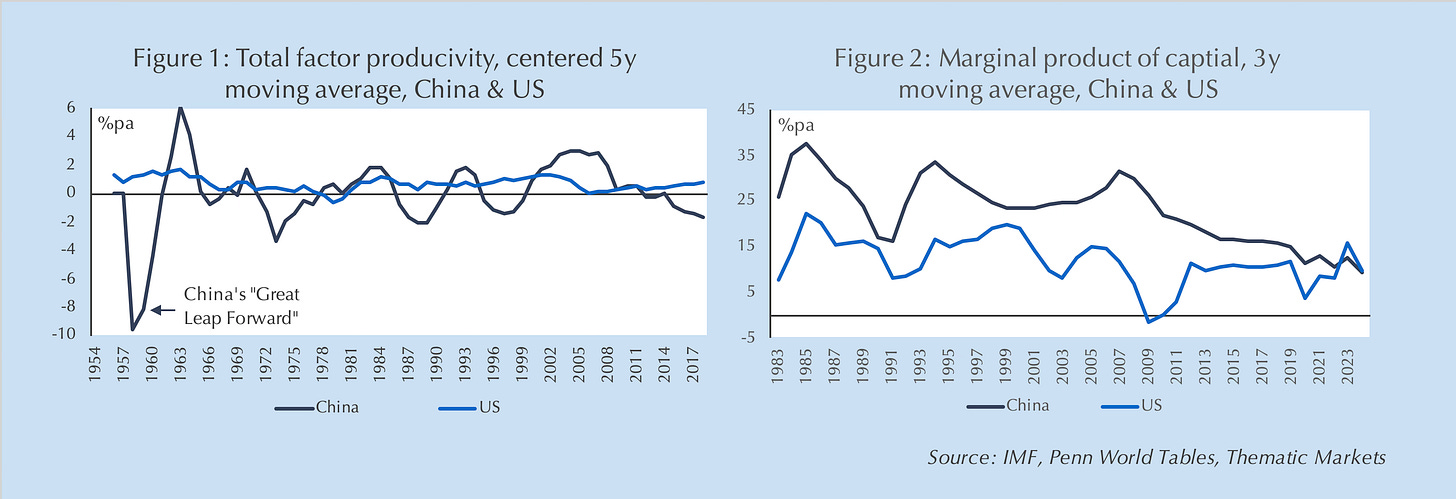

Yet, contrary to another popular myth, China’s rise has little to do with efficiency or productivity. China’s ascent results mostly from beggar-thy-neighbor industrial policies. China’s total factor productivity (TFP) growth – growth in output not resulting from adding more labor or capital, i.e. efficiency and innovation – has been negative for nearly a decade (Figure 1); i.e. more than all of China’s growth since 2013 has come from increasing capital, even as efficiency subtracted from output.13 As a middle-income country, China should offer higher returns on investment than an already rich country, yet the marginal product of capital in China had fallen below that of the United States (Figure 2). Put another way, China’s economy now is so inefficient that it requires an extraordinary $11 of investment to create $1 of incremental of output. Furthermore, these figures likely understate China’s inefficiency since they are based on reported Chinese GDP growth that probably is overstated.

Current hyperventilation over China’s massive overcapacity in autos is a case in point. In 2023, China’s installed capacity for automobile production was 48.7 million units, almost three times domestic sales, over half of global demand, and nearly double the capacity of the next largest automaking region, Europe.14 In no market economy where capital is allocated based on prospective return would profit-driven businesses risk building that much excess capacity in an industry that averages 4-5% profit margins.15

Overcapacity is both endemic to China and an intentional policy choice

Which of course begs the question of why the Chinese policymakers directing its industrial policy would create massive overcapacity, not just in autos, but in industry after industry.16 When China was a poor country with a relatively small share of the global economy, its beggar-thy-neighbor industrial policies made economic sense, and to Chinese policymakers’ credit, these policies lifted more people out of poverty than any other government in history. But the same policies make little economic sense for the world’s largest manufacturer with arguably the most modern capital stock of any economy. Yet given the CCP’s remarkable success in rapidly transforming China from a poor, underdeveloped nation to an economic, military and geopolitical colossus, it would be a mistake to assume that the persistence of widespread overcapacity in China is a policy error rather than a policy choice.

It also would be a mistake to ignore CCP policymakers’ – particularly President Xi Jinping’s – clear statements of intent. For nearly 30 years, Chinese political, military and diplomatic doctrine has been to use economic development to raise China to a position where it could challenge and displace the US-dominated world order. President Xi has been unabashedly clear in his desire to create a new “multipolar” order that returns China to its historic role as the ”Middle Kingdom.”17 He has been similarly blunt that he expects and is preparing for war with the West that he aims to win.18 Mr. Xi’s top international and domestic policy priorities – the “Made in China 2025” and Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – aim to make China as self-sufficient as possible while placing it at the center of a new international order based on dependencies to China that guarantee the domestically unavailable resources. “Economic” policy was realigned by President Xi to meet those priorities: growth no longer is the focus; national security, self-sufficiency and social stability are.19 The centerpiece of the new economic policy is President Xi’s “Dual Circulation” concept: self-sufficiency at home and reorienting international trade and investment as vectors of statecraft.20

Overcapacity is a feature, not a bug

Against this backdrop, one should view China’s systematic overcapacity in strategic industries as a feature, not a bug. While it incurs an obvious economic cost – that Chinese policymakers appear happy to bear – overcapacity simultaneously achieves three strategic objectives:

It undermines China’s adversaries’ capacity for industrialized (i.e. sustained) warfare by “dumping” its excess production at predatory prices in adversaries’ markets, shuttering their (market-driven) producers. The war in Ukraine has belatedly but clearly illustrated both Western military powers’ diminished munitions inventories and, more importantly, limited ability to restock from domestic production. The rapid rise of China’s navy also accompanies an equally astonishing takeover of global shipbuilding, where China now holds a greater-than-50% market share.21

Over capacity also induces Chinese dependencies, particularly in the “non-aligned” world, by exporting affordable manufactured luxuries (e.g. cars) and technology (e.g. 5G telephone networks) to developing economies in exchange for secure sources of mineral resources, cementing China’s position as the Middle Kingdom of a new BRI-shaped world order.

Third, and perhaps most important to my economic analysis below, it supercharges China’s scientific and technological progress in competition for leadership with the US. Autos are, again, an excellent example of the principle: China’s electric vehicle exports are not just cheaper and more numerous, but increasingly described as more advanced, both in features offered and technology. Unleashing 241 automakers across Chinese provinces with subsidized capital to compete both within China’s tariff-protected market and competitive-capital export markets22 is economically inefficient – guaranteed to produce over capacity and large losses – but is an excellent means to promote technological progress and knowhow that propels Chinese manufacturers to the forefront of the production possibilities frontier.23

While it is easy to see China’s doctrine of “Unrestricted Warfare” everywhere if one wants to, it is difficult to reconcile the combination of persistent, large-scale, economically wasteful industrial policy, its concentration in industries strategically important for national security, and China’s escalating belligerence, both rhetorical and actual, with any conclusion other than that its industrial policy is based in national security, not economics or market-determination.24

Increasingly incompatible: Chinese industrial policy

Whether one accepts that Chinese industrial policy is grounded in national security rather than economics policy, in an economy as large as China’s, the persistent overcapacity that it results in is incompatible with sustainable free-trade policies in Western economies and may be wholly incompatible with market-based systems. The irreconcilability of China’s system is rooted in two increasingly rigid political realities and one underappreciated economic effect that is the primary focus of this article.

The implacable political realities are that free trade with China is politically unsustainable in Western democracies and represents a growing threat to geopolitical stability. Leaving aside the question of intent, China’s export blitzkrieg is having the practical effects outlined above: eviscerating one strategic – and high-paying – manufacturing industry after another, across advanced economies, leaving angry, displaced workers and decimated communities in its wake, and simultaneously undermining those economies’ ability to meet their own critical needs and security. While the underlying driver of the Politics of Rage – the growing populist backlash across advanced economies – is a sense of political disenfranchisement, one of its most powerful channels of transmission has been the economic dislocation caused by free-trade policies that many workers opposed, as well illustrated by the “China shock” authors.25

Similarly, rising recognition of China’s strategic threat to security increasingly aligns not only Democrats and Republicans in Washington, but the US with its Pacific and Atlantic allies more strongly than at any time since the Cold War (and is even drawing in new allies like India). At the same time, the war in Ukraine and Covid laid bare that the West is woefully ill prepared to fight an attritional, industrial war or even meet its own critical needs in an emergency as it now lacks sufficient industrial capacity after decades of “outsourcing,” mostly to China, its greatest adversary.26

One group, however, has fiercely resisted counter-industrial policies – subsidies, tariffs and controls on critical technology – economic liberals and many academic economists. Objections are grounded in a range of views: a mistaken view that China’s economic gains result from market-based efficiency rather than industrial policy;27 erroneous belief that market constraints are binding on Chinese investment, production and pricing decisions;28 Economic theory that trade retaliation is welfare destructive and inefficient;29 and ideological purity that Western economies must be a standard bearer for free markets or slip towards statism themselves.30

But the reality is that China’s industrial policies not only are politically and geopolitically destabilizing, but economically inefficient and a drag on global welfare. Just as monopolies result in economic losses by undercutting competitors that may be more productive and generate higher welfare, national-security driven industrial policy that is intended to eliminate strategic competitors to China reduces global welfare by eliminating potentially more productive and higher-value-added producers elsewhere. A closer look at manufacturing in advanced economies, particularly the US, suggests this is indeed occurring.

The mysterious disappearance of US manufacturing productivity growth

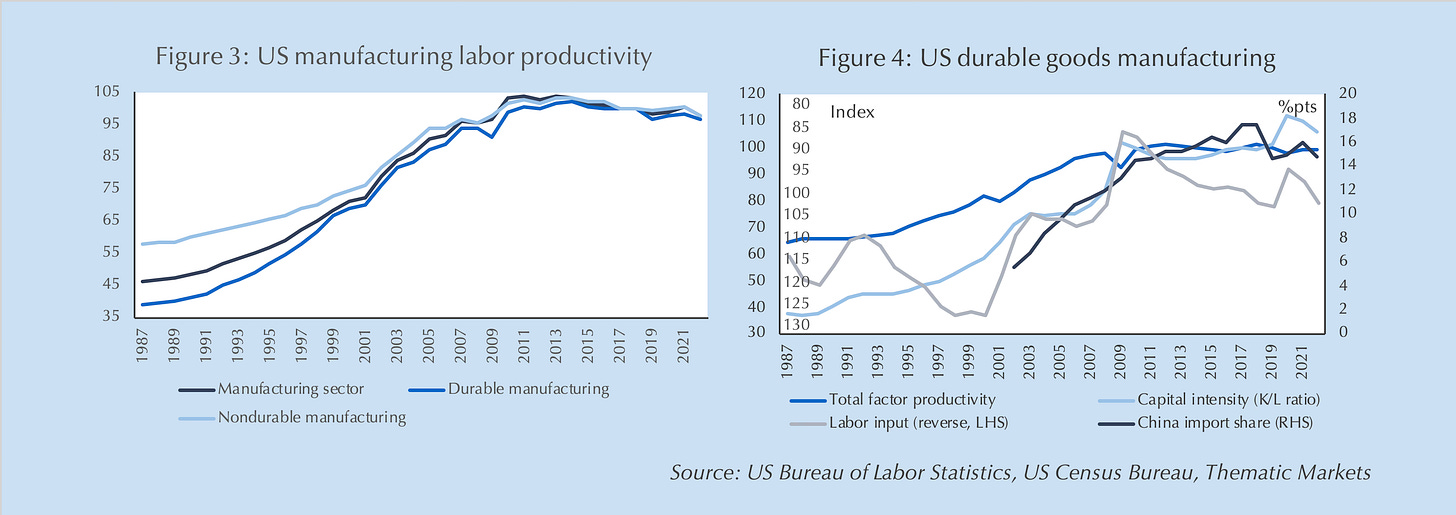

Labor productivity in US manufacturing peaked in 2008 and has been declining since (Figure 3). This disturbing trend is even more startling given that it came on the heels of the late 1990s-early 2000s US “productivity miracle.” The most notable change in trend has been in durable manufacturing and is mirrored by that in other advanced economies like Germany and Japan (not shown).31

Competition is good…when it’s healthy

Figure 4 breaks US durable manufacturing productivity into three of its component parts32 – labor input (grey, inverted), capital intensity (or the capital/labor ratio, pale blue) and total factor productivity (TFP, royal blue) – and compares them to import penetration of Chinese durable manufacturers (dark blue).33 Contrary to the late 1990s when the “productivity miracle” spurred US manufacturing to increase employment, US producers initially reacted to the competitive challenge of surging Chinese imports by sharply curtailed labor input and increased capital per employee (capital intensity). The result was not only a rise in overall labor productivity, but an increase in TFP as US firms, squeezed by Chinese competition, found new ways to eke out additional output beyond their capital and labor inputs.

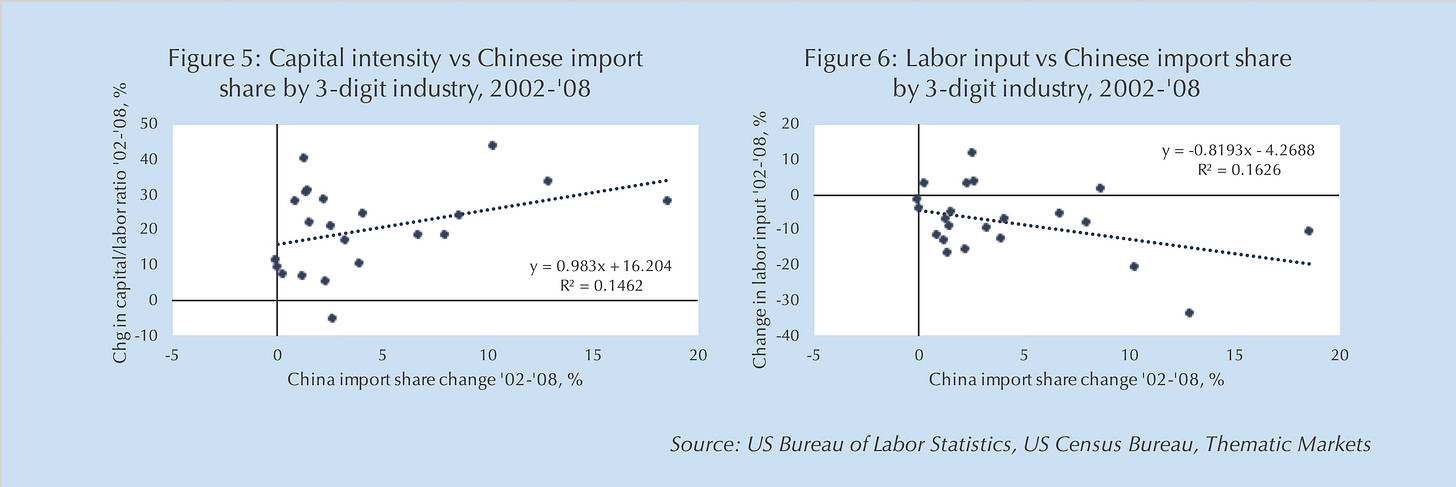

This early response to Chinese imports – which seemed to validate the view that healthy competition results in innovation – also was visible on an industry-by-industry basis (3-digit NAICS level) as shown in Figure 5 and 6, where labor input was negatively correlated with Chinese import penetration and capital intensity was positively correlated.34 Yet it is worth noting that this period, the primary window of study for the “China shock” authors, was a period of “healthy” competition that witnessed brisk TFP gains in China as its early stage of development allowed for rapid efficiency gains (Figure 1). Yet, over the same period other researchers found that Eastern European countries’ TFP gains had an even more significant positive effect on advanced economies’ productivity than China.35

China’s shift to capital-subsidized growth drives out competitors

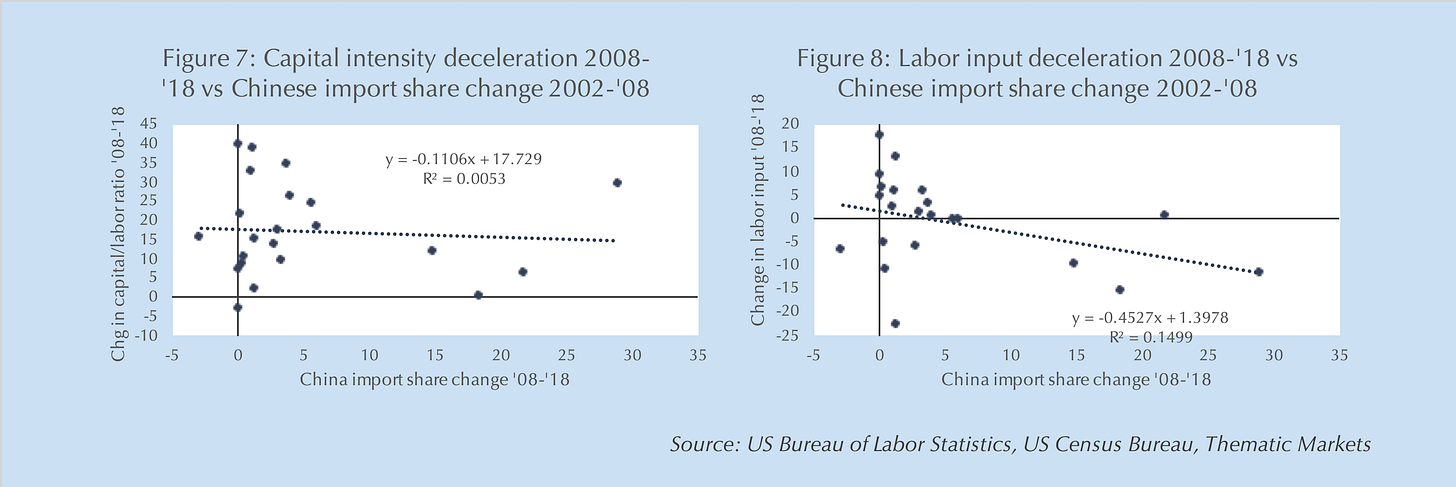

But by the 2010s, US (and other advanced economies’) manufacturers changed tack as Chinese TFP gains were replaced by state-subsidized capital deepening. Unable to compete with land grants, effectively non-recourse subsidized loans for factories and machinery, and subsidies for exports, Western producers stopped trying to compete. During this period, as shown in Figures 7 and 8, the more exposed to Chinese competition US producers were, the more they retreated from capital investment, leading to flat or falling capital intensity, and the more they shed workers to contain costs. Martin Fleming of the Productivity Institute shows that during this period US manufacturers’ behaviour was consistent with a shift towards extraction of gross operating surplus (profit margin) from existing capital, i.e. squeezing out as much profit from its remaining life while winding down the business, rather than investing in future production capacity.36

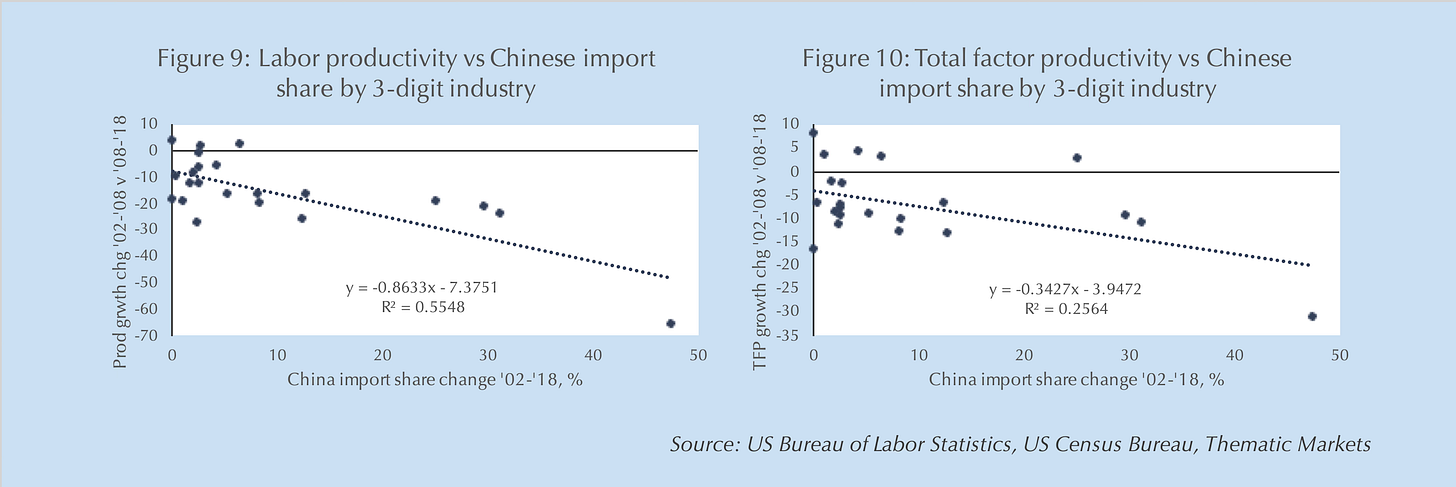

The net effect of US manufacturers’ response to China’s subsidized-capital model of export growth was a decline in US labor productivity over the course of the last decade. Figure 9 illustrates that the more exposed to Chinese import competition the industry, the worse was its labor productivity growth. More troubling still, the decline in productivity was not solely due to declining capital-to-labor ratios. As shown in Figure 10, increasing competition from Chinese imports was associated with a decline in TFP, too. Consistent with Martin Fleming’s analysis, the “China shock” authors recently showed at a firm-level that increasing competition from China led to declines in R&D spending and patent filings.37 Other economists have found a similar firm-level response to competition from Chinese firms in France.38

Irretrievable “learning by doing”

But the TFP fall in US manufacturing likely reflects more than just a decline in research and product development: it almost surely also reflects a drop in “learning by doing” (LBD). LBD is difficult to measure, but previous studies have shown that it is an important source of total TFP growth that – critically – tends to be firm or even factory specific, and tends to be actively cultivated by a combination of management and investment.39 Hence, when the owners of a factor shift their focus from competitive expansion to surplus extraction, downshifting investment and shedding skilled labor in the process, LBD growth is undermined. Worse still, it is lost forever when the factory is shuttered.

The role of Chinese imports in suppressing LBD appears corroborated by US Census Bureau data on dispersion of TFP among manufacturing firms.40 TFP dispersion in US manufacturing notably increased after China’s 2001 WTO accession (Figure 11). Increasing dispersion and the rising TFP that accompanied it in the first decade of the “China shock” would be consistent with LBD diffusion as firms differentially reacted to surging competition from China.41 However, high levels of dispersion continued over the decade, even as TFP growth stalled and began to fall. Without new LBD, diffusion should have reduced dispersion. Its sustained elevation suggests instead a diffusion of negative TFP growth – i.e. differential firm-level withdrawal from competition and focus on surplus extraction – that results in a dispersion of skill loss and negative LBD productivity growth. Figure 12 breaks firm-level TFP dispersion down by 3-digit industry and compares it to import competition from China. Again, like falling TFP itself, the degree of TFP dispersion among firms within an industry is correlated with Chinese import penetration.42

Talent goes elsewhere, worsening the problem

LBD declines in manufacturing likely were furthered both by human capital destruction and by diverting the highest human-capital workers to other activities. The “China shock” authors well demonstrated the permanent welfare loss suffered by the displacement of older, less-educated workers that had greater difficulty changing industries and consequently dropped out of the labor force.43 Angus Deaton and others have documented the far greater social and human costs of their dislocation, in terms of addiction, crime and suicide.44 But less researched is the effect on the best and brightest workers, and the effects of their employment choices on US productivity.

Both anecdote and intuition suggest that workers with the highest human capital – and most choice – shifted to industries facing less competition from (or perhaps even benefitting from) Chinese state-capitalism. The US industries that saw increasing productivity growth from the first decade of the millennium to the second were all industries outside manufacturing that were less exposed to the “China shock”: rental and leasing services (NAICS 532-533), software publishing (511), management services (55), computer design (5415), oil and gas extraction (211), mining (212), and arts and entertainment (71). By discouraging high-human capital workers from entering manufacturing, especially at a time when technology potentially is making LBD more human-capital intensive, the “China shock” likely further depressed manufacturing productivity.45

Welfare losses are global, not local

It is important to note that the productivity losses that plagued the US and other advanced economies since 2008 and appear to be driven by non-market-based Chinese industrial policies were not offset by welfare gains elsewhere. As noted, China suffered negative TFP growth over most of this period and financed its non-economic capital deepening with a staggering domestic debt load that will weigh on its citizens’ consumption for a decade or more. Nor have other emerging markets, most of whose per capita incomes ceased converging with advanced economies about the same time, benefitted. Hence, China’s industrial policies appear to be leading to a global welfare loss.

Toward a bifurcated global economy

In Global entropy: Enter the dragons, I stipulated that we are moving towards a bifurcated global political economy with the Anglo-sphere on one side and a China-Russia axis on the other. The pillars of – and sources of power within – that bifurcated global economy will be technology and critical resources. The Anglo-sphere has both, while China and Russia are married by the former’s technological leadership and the latter’s natural resources.

China’s national-security-based industrial policy is hastening the bifurcation. Attitudes towards both China and its exports have shifted sharply in recent years. With each passing day the political infeasibility of free integration of China’s economy into Western market-oriented economies becomes clearer. An increasingly bipartisan consensus recognizes that China’s economy is simply too large for the West to continue to accommodate its industrial policies and intentional overcapacity. Similarly, the national security risk posed by China’s asymmetric manufacturing capacity is gaining recognition across party lines and Western capitals.

These dual political realities are pushing the West to slowly separate itself from China’s economy, while sanctions on Russia are simultaneously pushing it ever more firmly into China’s orbit and furthering the separation with the West. The US has increasingly turned to subsidies for domestic producers, tariffs on Chinese goods, and export controls on critical technologies. Europe has been slower but is moving in the same direction. Concerns that these policies will undermine the “rules-based” order are misplaced. As I noted in Enter the dragons, Global entropy is by now well entrenched: the post-War liberal order already is largely disintegrated.

To preserve its rules in the Western half of the global political economy requires counter-industrial policies and an economic split with the China-Russia axis. Free-trade with a large, non-market economy like China is increasingly turning Western voters against free trade policies even with friendly, market-based economies. Furthermore, as shown by my analysis of the effects of Chinese trade on Western productivity, open trade with China is both facilitating its technological advancement and simultaneously undermining both Western industrial capacity and the technological progress that accompanies it. It is dangerously naïve to assume that Chinese policies will fail because they do not deliver growth; that is not their aim.46 The last quarter century has well proven their ability to propel China forward technologically, industrially, politically, and militarily, while concurrently retrograding Western prowess and power.

See The China Trade Shock website for associated research papers and commentary.

“Reassessing the Role of State Ownership in China’s Economy,” Stanford Center on China’s Economy and Institutions, 15 January 2024.

“CCP branches out into private businesses,” Jerome Doyon, East Asia Forum, 11 August 2023; and “Political governance in China’s state-owned enterprises,” Xiankun Jin, Liping Xu, Yu Xin, & Ajay Adhikari, China Journal of Accounting Research, vol. 15, no. 2, June 2022.

“Big Business and Cadre Management in China,” Kjeld Erik Brødsgaard & Kasper Ingeman Beck, Copenhagen Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 39, no. 2, 2021.

“Red Ink: Estimating Chinese Industrial Policy Spending in Comparative Perspective,” Gerard DiPippo, Ilaria Mazzocco, Scott Kennedy, & Matthew P. Goodman, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 23 May 2022.

Ibid.

“Schumpeter in Practice: The Role of Credit for Industrial Policy in China,” Lisa Geißendörfer & Thomas Haas, working paper, University of Würzburg, October 2022.

“China’s problem is excess savings, not too much capacity,” Michael Pettis, Financial Times (Op-Ed), 30 April 2024; “Global Clout, Domestic Fragility,” David Dollar, Yiping Huang & Yang Yao, Finance & Development, International Monetary Fund, Summer 2021; “Assessing China’s Financial Reform: Changing Roles of the Repressive Financial Policies,” Yiping Huang & Tingting Ge, Cato Journal, Winter 2019; and “China's Financial Repression: Symptoms, Consequences and Causes,” Guangdong Xu, The Copenhagen Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 36, no.1, July 2018.

“China is the world’s sole manufacturing superpower: A line sketch of the rise,” Richard Baldwin, VoxEU/CEPR, 17 Jan 2024.

“The Hamilton Index, 2023: China Is Running Away With Strategic Industries,” Robert D. Atkinson & Ian Tufts, Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, 13 December 2023.

Critical Technology Tracker, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, updated 22 September 2023.

Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, Annual Report to Congress, US Defense Department, 2023.

Negative TFP growth may seem at odds with my contention (below) that one motivation for Chinese overcapacity is to increase the pace of “learning by doing”, but it is not: overcapacity accelerates the pace of learning by doing but is still economically inefficient, i.e. Chinese industrial policy is prioritizing time over its citizens’ (and others’) welfare by allocating more capital and labor resources than would be economically (cost) efficient.

“The polarisation of China’s automobile production capacity,” Nan Zhang, Just Auto, 12 December 2023; “Global Vehicle Sales Top 92 Million Units in 2023; December Volume Up 11%,” Haig Stoddard, Wards Intelligence, 30 January 2024; and “China's car exports hit record high in April, as domestic sales fall,” Qiaoyi Li & Brenda Goh, Reuters, 10 May 2024.

N.B.: current average margins are nearer 8%, but this reflects a temporary bump from Covid-related supply shortages. “Automotive Profitability: How OEM and Supplier Margins Are Faring,” Klaus Stricker & Pedro Correa, Bain & Company, 21 November 2023.

“China’s overcapacity so ‘deeply rooted’ at local levels that analysts say its ebbs and flows have underpinned economy for decades,” Ji Siqi, South China Morning Post, 21 May 2024; “China’s overcapacity ‘problem’ in five charts,” Research Briefing, Oxford Economics, 17 May 2024; and “Breaking down Janet Yellen’s comments on Chinese overcapacity,” Hung Tran, Atlantic Council, 9 April 2024.

“China’s Vision for World Order,” Johanna M. Costigan, China File, 7 December 2023; China’s Approach to Global Governance, Council on Foreign Relations; and The Third Revolution: Xi Jinping and the New Chinese State, Oxford University Press, 3 May 2018.

“Xi Jinping Says He Is Preparing China for War,” John Pomfret & Matt Pottinger, Foreign Affairs, 29 March 2023; “China's Xi calls for combat readiness as PLA marks founding anniversary,” Greg Torode & Albee Zhang, Reuters, 1 August 2023; “Xi Jinping tells China's PLA to intensify preparations for war,” Firstpost, 6 July 2023; and “Xi Jinping urges China’s military to be ready for war in uncertain and unstable times,” Liu Zhen, South China Morning Post, 9 November 2022.

“For Xi Jinping, the Economy Is No Longer the Priority,” Guoguang Wu, Journal of Democracy, October 2022; and “Xi Jinping Drops Economic Growth for ‘Values-Based Legitimacy’,” Chris Anstey, Bloomberg, 21 October 2023.

“Xiconomics: What China’s Dual Circulation Strategy Means for Global Business,” Patrick McAlary, Centre for Geopolitics, University of Cambridge, 13 September 2023; “Dual circulation in China: A progress report,” Hung Tran, Atlantic Council, 24 October 2022; “Will the Dual Circulation Strategy Enable China to Compete in a Post-Pandemic World?” China Power, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 15 December 2021; and “What is behind China's Dual Circulation Strategy?” Alicia García-Herrero, Bruegel, 7 September 2021.

“The Threat of China’s Shipbuilding Empire,” Matthew P. Funaiole, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 10 May 2024; “China cements position as world’s top shipbuilder in 2023,” Katherine Si, Seatrade Maritime, 16 January 2024; and “China Is Still the King of Shipbuilding, Data Shows,” Aadil Brar, Newsweek, 3 January 2024.

“How you export matters: Export mode, learning and productivity in China,” Xue Bai, Kala Krishna & Hong Ma, Journal of International Economics, vol. 104, January 2017.

“The polarisation of China’s automobile production capacity,” Nan Zhang, Just Auto, 12 December 2023.

Unrestricted Warfare was a 1997 book by two then senior colonels in the People’s Liberation Army, Major General (ret.) Qiao Liang and Colonel (ret.) Wang Xiangsui, that advocated, as the title suggests, an unrestricted definition of warfare that extends beyond military conflict to all domains, specifically enumerating economics, politics, international law, and information. There are several translations of the book to English and an abridged version created by the US Foreign Broadcast Information Service is available free online. David Kilcullen discusses the risk of seeing “unrestricted warfare” everywhere in his book, The Dragons and the Snakes, Hurst, March 2020.

“Importing Political Polarization? The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure,” David H. Autor, David Dorn, Gordon H. Hanson, & Kaveh Majlesi, American Economic Review, vol. 110, no. 10, October 2020.

“The EU Defence Industrial Strategy: solution to or distraction from Europe’s rearmament dilemma?” Jocelyn Mawdsley, UK in a Changing Europe, 9 April 2024; “The Attritional Art of War: Lessons from the Russian War on Ukraine,” Alex Vershinin, Royal United Services Institute, 18 March 2024; “Time to strengthen European defence industry,” Josep Borrell, EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, European Commission, 11 March 2024; “Ready for War?” Defence Committee Report, UK House of Commons, 4 February 2024; “The U.S. Defense Industrial Base Is Not Prepared for a Possible Conflict with China,” Seth G. Jones, Center for Strategic & International Studies, 2024; “The West can no longer make war,” Malcom Myeyune, The New Statesman, 1 August 2023; “The Guns of Europe: Defence-industrial Challenges in a Time of War,” Hannah Aries, Bastian Giegerich & Tim Lawrenson, International Institute for Strategic Studies, 19 June 2023; “Military briefing: Ukraine war exposes ‘hard reality’ of west’s weapons capacity,” John Paul Rathbone, Sylvia Pfeifer & Steff Chávez, Financial Times, 2 December 2022; and “The Insufficient Industrial Base,” Sgt. Maj. Stephen Minyard, NCO Journal, Army University Press, 4 October 2019.

E.g. the “China shock” authors’ assume Chinese export growth results from exogenous productivity gains and cite high rates of measured productivity growth in the early 2000s, which admittedly is the period of their study; see “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States,” David H. Autor, David Dorn & Gordon H. Hanson, American Economic Review, vol. 103, no. 6, October 2013.

“Does National Security Justify Tariffs?” Jon Murphy, Econlib, 7 May 2018.

International Economics: Theory and Policy, Paul R. Krugman & Maurice Obstfeld, Pearson, 12th edition, 12 June 2023.

“The (Updated) Case for Free Trade,” Scott Lincicome & Alfredo Carrillo Obregon, Cato Institute, Policy Analysis no. 925, 19 April 2022; and “The Fight for Free Trade,” Tori Smith & Riley Walters, The Heritage Foundation, 8 May 2020.

“Productivity Profile of Germany” and “Productivity Profile of Japan”, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, updated as of 27 May 2024.

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) breaks down contributors to labor productivity further, including the effects of materials, services and intermediate inputs in its disaggregation, hence the three components that I list – using BLS data – are not complete, but are representative of the underlying trends.

The China import share is not the share of domestic expenditures by value, but is calculated as the ratio of the value of Chinese imports in each sector to the value of domestic production.

In my analyses I excluded a few outliers that skewed the results but were fundamentally consistent with them: Apparel and leather manufactures (SIC 315-316, combined in the Census trade data on China) were removed because import penetration from China was multiples of domestic production that had already largely shifted abroad due to earlier import competition. Oil & gas extraction (NAICS 211) and mining (NAICS 212) were removed for the opposite reason: Chinese import penetration was too low. In both cases, however, the direction of the effects was consistent with the analysis presented: the massive increase in Chinese imports of apparel were associated with the largest drop in productivity of any 3-digit industry, while oil & gas, which faced little Chinese competition had the highest productivity gains in the 2020s.

“The China Effect on Manufacturing Productivity in the United States and Other High-income Countries,” Daniel Lind, International Productivity Monitor, Centre for the Study of Living Standards, vol. 42, Spring 2022.

“Manufacturing Sector Producvity Collapse: A Tale of Two Technologies and One Giant Competitor,” Martin Fleming,The Productivity Institute, in process, 26 October 2023.

“Foreign Competition and Domestic Innovation: Evidence from U.S. Patents,” David Autur, David Dorn, Gordon H. Hanson, Gary Pisano, & Pian Shu, American Economic Review: Insights (forthcoming), January 2019.

“Opposing Firm-Level Responses to the China Shock: Horizontal Competition versus Vertical Relationships?” Philippe Aghion, Antonin Bergeaud, Mattieu Lequien, Marc Melitz, & Thomas Zuber, NBER Working Paper 29196, November 2022.

“Productivity Growth and Input Demand: The Effect of Learning by Doing in a Gold Mining Firm in a Developing Economy,” John Baffoe-Bonnie, International Economic Journal, vol. 30, no. 4, 8 August 2016; “Toward an Understanding of Learning by Doing: Evidence from an Automobile Assembly Plant,” Steven D. Levitt, John A. List & Chad Syverson, Journal of Political Economy, vol. 121, no. 4, August 2013; and “Productivity Adjustments and Learning-by-Doing as Human Capital,” Jim Bessen, Center for Economic Studies, US Census Bureau, Working Papers 97-17, 20 August 1997.

Hat tip to Joseph Politano at Apricitas Economics for alerting me to these data’s existence as I was writing this piece; see “America’s Manufacturing Productivity Problem,” Joseph Politano, Apricitas Economics, 14 May 2024.

“Learning by Doing, Productivity, and Growth: New Evidence on the Link between Micro and Macro Data,” Brad R. Humphreys, Scott Schuh & Corey J.M. Williams, West Virginia University, Working Paper 24-02, February 2024.

This relationship holds in both the 2002-’08 and 2008-’18 subsamples.

“The China Shock: Learning from Labor-Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade,” David H. Autor, David Dorn & Gordon H. Hanson, Annual Review of Economics, vol. 8, October 2016; and “The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States,” David H. Autor, David Dorn & Gordon H. Hanson, American Economic Review, vol. 103, no. 6, October 2013.

Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, Anne Case & Angus Deaton, Princeton University Press, 17 March 2020; “Labor markets and incarceration: The China shock to American punishment,” John Clegg & Adaner Usmani, Criminology, vol. 61, no. 4, 25 October 2023; “When Work Disappears: Manufacturing Decline and the Falling Marriage Market Value of Young Men,” David Autor, David Dorn & Gordon Hanson, American Economic Review: Insights, September 2019; and “Free trade and opioid overdose death in the United States,” Adam Deana & Simeon Kimmel, SSM – Population Health, 8 August 2019; and “The Transformation of Manufacturing and the Decline in US Employment,” Kerwin Kofi Charles, Erik Hurst & Mariel Schwartz, NBER Macroeconomics Annual, vol. 33, 2018.

“Innovation and Productivity: Is Learning by Doing Over?” Ružica Bukša Tezzele, Economic and Business Review, vol. 24, no. 1, March 2022.

“China’s Quixotic Quest to Innovate,” George Magnus, Foreign Affairs, 29 May 2024.