For anyone involved in markets (or trade negotiations!) it’s been a rough couple of weeks. Even my crystal ball broke. Despite correctly predicting the ambitious scale of the Trumpian Revolution and warning that markets significantly underestimated the magnitude and permanence of coming tariffs, my portfolio recommendations blew up as a combination of growth fears, loss of faith in US policymaking and cascades of deleveraging wrought carnage in markets. (Don’t cry for me: my top recommendation for 2025 was to be long volatility of volatility, which has performed spectacularly.)

The greatest irony is that when I correctly forecast Mr. Trump’s unexpected 2016 win – and more importantly what he represented – I wrongly expected markets to react as they did this past week. Instead, they rallied on perceptions that, however obnoxious, he is just another Republican. This time I wrongly assumed that after eight years and a detailed Jacksonian campaign platform that was validated as more than rhetoric by radical cabinet picks, that markets had come to understand, as I have consistently warned, that President Trump is not a Republican but MAGA. He embodies the Politics of Rage’s complete rejection of both the center-left/right consensus that has ruled Western democracies for 80 years and the post-War liberal order (PWLO) that it created. Markets got a painful lesson in those statements’ truth while I got (another) lesson not to assume my own views as common knowledge.

The PWLO is dead! Long live La Cosa Nostra Americana!

As I’ve written before, President Trump is not the PWLO’s destroyer but instead a manifestation of its death. Markets’ reaction to the arrival of the Trump Comet announcing the PWLO’s passing mirrors the Kübler-Ross stages of grief. Initial mockery of the Trump Administration’s “reciprocal” tariffs – “Stupid!”, “Economically illiterate!”, “Generated by ChatGPT!” – reflected elites’ and markets’ shock and denial. But denial rapidly evolved to anger and bargaining as it became apparent the Trump Administration was serious. Throughout, a background chorus arose that has been cited to justify markets’ panic: “The end of American exceptionalism.”

But what exactly does American exceptionalism mean? As Mark Farrington, one of the sharpest observers of markets I’ve met in my three-decade career, observed, the phrase has become vacuous. To most Americans it is a belief that America was destined by God (or perhaps Gaia) to be a “shining city upon a hill,” a beacon of virtue and an example of propriety for both the corrupt “Old World” and the unlearned savages of less developed countries. To most of the rest of the world American exceptionalism was a free guarantee of security and unfettered trade that earlier generations, who had suffered the insecurity that characterized most of human history before World War II, appreciated as American beneficence but that later generations have come to take for granted. Some, like the French, even jealously resent it as “exorbitant privilege.”

American exceptionalism, as Mark notes, is multifaceted and its foundations are not easily assailed, even by President Trump’s Jacksonian assault (recall that 200 years ago a much younger America survived the original Jackson). The Trump administration’s torrential, erratic and poorly messaged attempt to force through a new world order of La Cosa Nostra Americana has rightly strained faith in the US policy framework. Yet the underlying shock, markets’ long-overdue recognition of the death of the PWLO, is even greater. Unfortunately, that realization doesn’t appear complete. Markets’ short-term rallies on each tariff pause or reversal suggest that they believe that, just like Elvis, the PWLO lives. Until markets accept that the old order is irretrievably gone – Kübler-Ross’s final stage of grief – it will be difficult for them to find a bottom.

Another source of confusion and panic stems from catastrophizing over the tariffs’ impact. Because large-scale tariffing by the world’s final consumer and hub economy within the complex web of modern supply chains is unprecedented, markets’ expectations are unanchored and many assume the worst. A personal anecdote illustrates the uncharted territory we’re entering. On “Liberation Day,” coincidentally, I happened to be at a dinner of about a dozen illustrious economists – all top academics including a Nobel laureate and a few former senior policymakers – gathered to discuss, of all things, fiscal policy. Yet, when asked, none could answer whether income taxes or tariffs had a greater effect on growth per dollar of government revenue raised. Markets don’t appear to have greater insight.

The answers to both of these questions – whence American exceptionalism and what effects tariffs will have on whom – are necessary inputs to resolving the final Uncertainty markets must overcome: how much further do markets go? Is this a standard (albeit ferocious) washout of overlevered positions? Or is it the start of a broader asset allocation shift?

I’ll tackle all three questions here: what happens to American exceptionalism in the post-PWLO world; how to handicap tariffs’ fiscal and economic effects; and how much further market adjustment needs to go.

Key insights

There is no Trump put. Tactical and negotiated retreats, yes, but large scale tariffs are here to stay.

Markets’ extreme gyrations reflect in part a delayed recognition that the post-War liberal order is dead and what will replace it remains uncertain. Risk premia on everything, including US Treasuries, should be higher as a result.

But American exceptionalism, properly understood as natural and immutable US advantages, will endure and, in a world of increasing Uncertainty, should command a greater premium.

From Waterloo to the Global Financial Crisis, reserve issuers have stumbled – amazingly even worse than the Trump Administration – and recovered. Time and success heal most wounds.

Tariff policy likely will be more successful than expected. Tariffs are remarkably understudied, relative to say fiscal policy, but simple, first-order analysis of their effects suggests the growth trade-off for the fiscal revenue they generate is significantly less than for income taxes.

In the US case, they are likely to further US advantages under Localization while disadvantaging US peers.

But now is no time to catch falling knives. Look instead in the direction others are running from: low-delta EURSEK and EURGBP puts are remarkably cheap, while 1y2y USD swaptions appear to underprice Fed paths in either direction.

Mapping terra nova

While I have written much over the last several years anticipating this week, as noted in the introduction, I somehow missed the trigger. Mea culpa. As a result I have done a lot of thinking over the last decade about what comes next.1 The answer, unfortunately, is profound Uncertainty.

The first step to narrowing that Uncertainty is accepting that the old world is gone and that large-scale tariffs and barriers to trade and investment will be the norm; i.e., there is no “Trump put.” What that implies for a new world order is more complex. But America will still be “exceptional” in that world – likely even more so – just differently. While this is terra nova, historical analogues do exist that can provide some guidance. Better understanding of tariffs’ effects, both on relative growth and the US fiscal position, will also help narrow uncertainty and may even (eventually) reaffirm lost faith in US policymaking. But all of this will take time for markets, still in shock, to digest. And not just markets. Other sovereigns, too, will play roles – both benign and malign – in solving for the a new world order.

Repeat after me: “There is no Trump put”

The first step to acceptance is recognizing that there is no “Trump put.” To see that consider that multiple sources – including personal acquaintances of mine with first-person experience – all testify that in his first term, President Trump displayed not only little knowledge of any policy issues but little to no interest in learning about them either. How then does one explain this previously ignorant, infamous egomaniac making the detailed plans described in Revolution for the fundamental transformation of American society, politics and economy when he ran (again) for a second term? There are only two explanations that withstand scrutiny: he is set on making a place for himself in the history books, or, more ominously, he has become a true believer. My suspicion is it is some measure of both.

President Trump has already achieved a remarkable comeback that makes him one of only two US presidents – already a select group of 45 men – to be elected to non-consecutive terms. But that isn’t enough. He doesn’t want to be one of the 40 or so US presidents that are or soon will be forgotten (even a history buff like me had to look up that Grover Cleveland was the other president to serve non-consecutive terms). No, Donald J. Trump wants to be remembered as one of those rare few who, love them or hate them, remade America: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Abraham Lincoln, or Mr. Trump’s historical doppelgänger, Andrew Jackson.

Alea iacta est

But immortalization requires two things: deep trauma and no looking back. If the transformation were easy or painless, no one would remember it. Likewise, only the forgettable in history turn back once the going gets tough. FDR didn’t reverse course building an expansive Federal government when faced with major reversals by the US Supreme Court (Schechter, 1935, and Butler, 1936) or even after the “Roosevelt recession” of 1937. Nor did Lincoln sue for piece and abandon unification after the Union Army’s disaster at Chancellorsville with General Lee marching on Pennsylvania. Similarly, Jackson brought the Union to the brink of dissolution in the Nullification Crisis, vetoed Congress’s establishment of the Second Bank of the United States, and ignored the Supreme Court’s reversal of the Indian Removal Act.

Donald Trump is 78 years old and is constitutionally prohibited from running for president again.2 He has been criminally convicted, compared to Adolf Hitler, and even many of his supporters are embarrassed by his behaviour. He has four years to make his mark on history. As Cæsar said crossing the Rubicon: the die is cast. There is no Trump put.

Tactical retreats are not a reversal

“But he has backtracked!” I hear you exclaim. He paused some tariffs when markets tumbled too rapidly, or in some electronics where the short-run damage to US firms would be too great, just as he did with the punitive tariffs on Canada and Mexico. The key words are paused and some. He has never backtracked on the steel and aluminum tariffs, and only pulled back the USMCA-compliant auto tariffs for Canada and Mexico once it became clear that repeated roundtrips of auto assemblies across North American borders made those tariffs multiples of the intended 25%.3 He also hasn’t back tracked from the baseline 10% tariff for from all countries including non-USMCA-compliant imports from Canada and Mexico. And he has doubled and even tripled down on tariffs on China, now at an astounding 145%. Meanwhile, the 90-day pause not only allows for negotiation, but acts as an effective “circuit breaker” for all global financial markets that were in free fall. No, this is not “four-dimensional chess” – the rollout has been an exemplar in churlish amateurism – but nor does it represent a reversal.

Acceptance requires more pain

As I noted in the introduction, markets’ continued belief in a Trump put suggests a lack of acceptance that the old order is dead. That means more pain lies ahead once the circuit-breaker pause comes to an end, which it will. That doesn’t mean that tariffs will return to their prior level. As I noted in La Cosa Nostra Americana, the tariffs fill three roles within the Trump policy mix: (1) incentivize US re-industrialization, (2) raise much needed revenue without discouraging capital investment, and (3) a coercive policy tool to force other countries to choose a side and rebuild if they’re going to be an American ally. The first two goals imply that meaningful tariffs are here to stay. But the third use of tariffs allows for a reduction in tariffs for countries that kiss the Don’s ring. Conversely, it also implies the potential for higher tariffs for those countries that do not.

What comes next?

But even when markets have accepted the death of the PWLO and the last country has negotiated a deal with Don Trump (or chosen Don Xi instead) – and that may take a while – markets will still be left with serious Uncertainty. That is because we can’t conclusively say what will take the PWLO’s place. While La Cosa Nostra Americana is the most likely form of geopolitical order to succeed the PWLO and seems to be the form that the Trump Administration seeks to impose, it may be only a transitory bridge to a new order. The PWLO was born of unassailable US military, economic and political power at a unique moment in world history 80 years ago. It died precisely because that is no longer true. The new order will be born in compromise that balances US and Chinese power within a constellation of regional powers. One model that may work is La Cosa Nostra Americana, but it isn’t the only one. The resultant Uncertainty implies that risk premia everywhere, even in US Treasuries, German bunds, or Swiss government bonds should be sustainably higher.

America’s God-given exceptionalism

Yet that doesn’t mean the end of American exceptionalism and I will be very explicit in what I mean by that: durably lower risk premia on American assets relative to other countries. “American exceptionalism” is not a reward for virtuous behavior. Capital markets don’t reward virtue; they reward risk-adjusted returns. And the US possesses both the most reliable return-generating economy and most secure sovereign polity in the world. Ironically, that is more true now amid the Uncertainty of Global entropy than during the height of American power at the end of the Cold War. If that seems paradoxical, think about European government bond yields over the last two decades since the birth of the euro: the premium for German bunds over periphery bonds is greatest when confidence in the European Monetary Union is its lowest.

Why is America less risky? Because it has been blessed by God (or conquest) with uniquely advantageous natural features that exist nowhere else and are bound by a strong but flexible legal covenant and cultural cohesion that has endured nearly 250 years. The US is exceptional because of its unparalleled set of strategic and economic advantages, including:

Economic geography: America has the world’s largest network of navigable rivers, notably the Mississippi-Missouri-Ohio River Basin, which with the Great Lakes network facilitates secure, low-cost, internal trade over 31 of the 50 US states and nearly 40% of its landmass. Those networks connect US trade to both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans providing easy access to all major global markets. US geography also is conducive to interconnecting road, rail and pipeline networks. Long, temperate growing seasons over most of the US and abundant highly productive arable land make the US one of the world’s largest agricultural producers.4

Geographic security: As President Trump is fond of saying, the US is securely protected by two huge oceans and is bordered by only two non-threatening (smaller) neighbors with whom it does most of its trade. Combined with its extensive natural internal trade networks, this gives the US exceptionally secure trade routes in times of war.

Natural resources: In addition to its abundant, highly productive agriculture, the US possesses nearly every natural mineral resource necessary in a modern economy, including huge deposits of copper, iron ore, gold, uranium, lithium, and rare earths (many still untapped). And of course, the US’s extensive hydrocarbon endowment – arguably greater than any country – has made it the world’s largest oil and gas producer.

Human capital and educational capital: The US’s 334 million people make it the third largest population country (fourth if one considers the EU as an entity), the only one among the top ten largest countries with a common language and culture, and with the EU and Japan, the only ones with a highly educated work force. A majority of the world’s top universities, think tanks and research institutions are American, and its venture capital “ecosystems” and entrepreneurial culture have better “brought to market” innovation than any other economy (save potentially China in recent years).

Military power: Although I have written a lot about the relative decline of American military dominance, its relative inferiority in the Western Pacific and the long-term strategic challenge it faces from China’s rapid rise, no other country can more credibly project its power anywhere than the US. Combined with its God-given natural defenses, at least for now, America is an impregnable fortress.

Cultural power: From Hollywood to social media, it is American media distribution platforms that dominate cultural diffusion and even definition. TikTok is an increasing influence, but the US has a commanding lead in cultural distribution.

Political resilience: The US is the oldest surviving constitutional democracy and the 5th oldest government in continuous existence. Over 249 years it has survived multiple intense periods of civil unrest, including civil war, multiple constitutional conflicts between the states and federal government, mass immigration waves, wars with other nations, depressions and financial crises, multiple monetary and tax regimes, and the “First Populist,” Andrew Jackson, on whom President Trump’s governing philosophy is based. While I do worry about civil unrest in the US amid serious internal divisions, America’s strong but flexible system of federalized government has proven a consistent ability to adapt.

Deep capital markets: US financial markets are peerless in size and liquidity. That will not change soon. Even if one imagined the unimaginable, the removal of all foreign participation, the largest and most active pools of capital in the world – US pension funds – would still make the US the king of capital markets. Further, its nearest competitors – the euro area and Japan – lack English common-law legal systems that have proven essential to develop the robust public and private debt, equity and derivative markets that exist in the US.

Credible institutions: The events of the last two weeks have strained many countries’ and market participants’ belief in US policy institutions, particularly their competence, but the US remains a nation with a rule of law where even the Trump Administration’s avalanche of executive orders have been carefully crafted in law, where those same policies have been successfully challenged by opponents in US courts, where the Federal Reserve has returned its focus to inflation, and the Treasury Secretary could convince a famously untameable president that a circuit-breaker pause in tariffs was necessary.

No other nation (nor the EU) can claim all of these advantages and few can claim to even be singly competitive with the US in any. Furthermore, only the last of them can realistically seen to have been damaged by the Trump Administration’s ham-handed implementation of a radical change in the global trading system. It is these advantages that make US debt and assets durably safer than their global peers: the foundations of the United States of America as a sovereign entity, its sources of physical, economic and social security, and its ability to reliably deliver stable growth and returns on capital are firmer than any other nation, making its debt and asset prices safer. That is what American exceptionalism, properly defined, means.

Yet the path to market realization of that definition may be slow and bumpy as it recovers from the shock of the last two week. Indeed, it could get much worse before it gets better. The severely misguided views of Trump advisors like Steven Miran and Peter Navarro on the US dollar and its reserve function are deeply dangerous and could precipitate a much sharper fall in the dollar if pushed further (or heaven forbid, forced on unwilling allies). Thankfully, the tariff “pause” – and multiple publicity photos released by the White House since, showing the President in the Oval Office with Secretary Bessent – suggest that Bessent, who understands international finance, is in ascendancy.

Historical analogues

Despite the unprecedented nature of recent events there are historical analogues from which we can draw lessons. Those analogues suggest that the dollar and dollar assets will remain core to the global financial system and that markets will learn to forgive and forget US indiscretions.

This is not the first time the US has given foreign investors cause to question the safety of their savings in US markets, even restricting ourselves to the modern era. Immediately upon taking office, Franklin Delano Roosevelt – who also radically transformed constitutional norms and governance in the United States (ironically the transformation Donald Trump now is trying to unwind) – devalued the US by 50% versus its gold peg, effectively defaulting and forcing a 50% haircut on foreign US Treasury holders. Less than 40 years later, Richard Milhouse Nixon delivered the largest shock to the post-War international financial system by abandoning the dollar’s gold backing and floating it versus other currencies. Years of subsequent Fed mismanagement of monetary policy, weak growth and deteriorating fiscal balances, pushed the dollar to its lowest levels ever on a real trade-weighted basis and tanked US Treasury prices in 1978.

While there was no real alternative to the US dollar in 1971 or 1978, that was arguably less true in 2008-’09 when the US was the epicenter of global crisis caused by regulatory and economic mismanagement that created a twin housing and banking crisis. Ironically, it was the Global Financial Crisis and its aftermath that exposed the serious underlying problems in both the banks and economic structure of the European Monetary Union (EMU), the only realistic alternative to the dollar as a reserve currency. That lesson should not be forgotten in the present circumstance where the safety of European debt and stability of EMU face graver threats (as I will discuss further in forthcoming research).

But perhaps the most dramatic example of markets losing faith in a reserve currency issuer – then gaining it back – was England and the gilt market during the Napoleonic Wars. Ahead of the Battle of Waterloo, gilt prices plunged to default-like levels as markets speculated that the United Kingdom might lose and either be invaded by France or forced to default. In an historical twist that parallels the current mistrust of the US by its allies: the UK’s allies in the war – Austria, Prussia and Russia –were deeply suspicious of the UK and as concerned about its pre-eminence as Revolutionary France’s. Yet, in the event, the UK triumphed and gilts surged in value, retaining their unique status as the world reserve asset for the next century. (For Economic History buffs, it was during this episode that economist David Ricardo reportedly made £1 million – a colossal sum then – speculating on gilts rebound.)5

Who’s afraid of Tariff Man?

One thing that might help US assets recover some of their shine is if Trump’s policy, even though erratically deployed, worked. Again, in part because of unfamiliarity in modern Economic history, many assume the worst from tariffs: that they will produce a stagflationary recession that worsens the deeply unsustainable US fiscal path, particularly in light of the Administration’s and Congressional Republicans’ intention to extend the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) income tax cuts. This sets up the potential for tariffs to positively surprise on all three fronts: growth, inflation and fiscal consolidation. In my last article I addressed the key variable determining inflation’s outcome – the Fed’s response – and how I expect that to play out. Thus, I’ll focus here on the fiscal and growth effects, which my calculations suggest are likely to be better than expected, underlying my relatively bullish view on the US economy (though I do expect volatile data this year).

A simple, first-order approach to growth and fiscal effects

Given the paucity of examples of large-scale tariff application in the modern era I take a simple, first-order approach to calculate their joint effects on fiscal and growth effects. As I noted in the intro, these joint effects are little researched and poorly understood by economists. Further, in my own calculations, as I explain below, I found that macro-level analyses are biased towards more negative growth effects when there are large bilateral imbalances in trade with some countries as is the case for the United States.

My approach is to assume conservatively (but not unrealistically) that 100% of the tariffs flow through to import prices that have a real income effect reducing private domestic demand in the economy and a substitution effect that lowers net imports. I also assume, again for conservatism, that all US trading partners retaliate by raising their tariffs on US exports by the same percentage point change the US applied to them. (I use the original “reciprocal” tariffs except for China where I assume the latest tariff as of writing, 145%.) I further assume that the real income effect is entirely absorbed in the first year when the price rise hits, but that the substitution effect takes place over three years, using short-run import price elasticities from the trade literature to calculate year 1 effects, and assuming that long-run substitution, given by long-run import price elasticities are evenly spread over years 2 and 3. Fiscal revenues are calculated as the tariff rate on the post-trade adjustment import values using short-run elasticities in year 1 and long-run elasticities in years 2 and beyond.

These first-order calculations lack dynamics (other than the switch from short-run to long-run trade elasticities) but are designed to be conservative – i.e. likely overestimating negative growth effects – as they assume consumers and business investment fully bear the tariff cost and there are no positive investment effects from the incentive to onshore production. The details are presented in the Appendix.

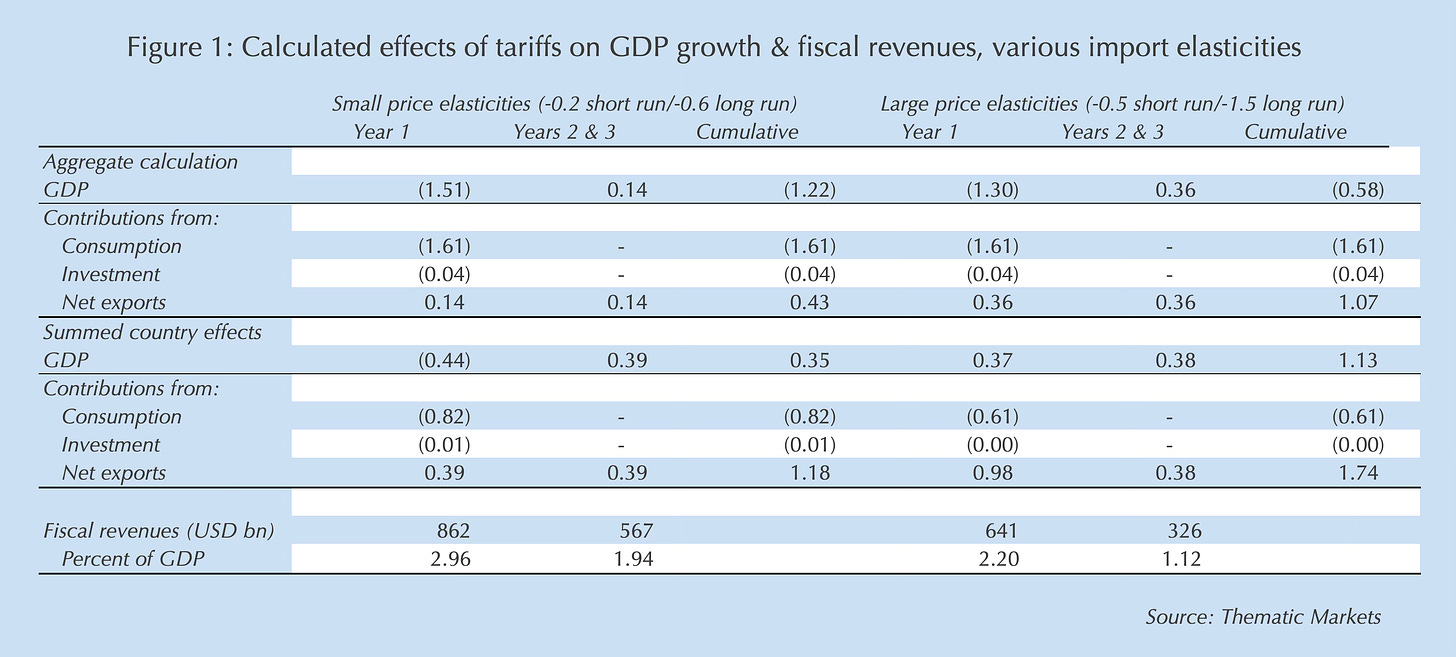

Despite my conservative approach I find relatively modest first-year effects on growth and net positive effects on growth in years 2 and 3 with a meaningfully large impact on fiscal consolidation. Figure 1 shows the modelled effects under both bottom- and top-of-the-range magnitude trade elasticities (-0.2 to -0.5 in the short run, -0.6 to -1.5 in the long run).6 The first four rows display the calculations using aggregate imports and the weighted-average increase in tariffs, which show a sizeable drag on US GDP: 1.3% to 1.5% in the first year and small gains from net exports in years 2 and 3 of 0.1% to 0.4% per year. On net, the three-year, cumulative effect is to subtract 0.6% to 1.2% from US GDP. Most of the drop, as expected, comes from a large negative real income effect that drags consumption down by 1.6 percentage points in year 1.

Caution necessary for aggregate estimates

But an interesting thing happens if I instead sum up the effects on trade from individual countries: the impact on growth is much lower. At lower trade elasticities, the first year drag on GDP growth is only 0.4%, and is fully offset over three years by net export gains of 0.4% in each of the subsequent years, leading to higher GDP over three years. The larger-magnitude elasticities produce even more positive results, with 0.4% higher GDP in year 1 and a cumulative three-year gain of 1.1%.

How is this possible? The answer lies in the mathematics of convexity around unbalanced trade and the structure of the Trump “reciprocal” tariffs. For countries with relatively balanced trade the retaliatory tariffs I assume imply that the combined negative income and export effects dominate the positive import substitution effect. But the greater the imbalance in trade, i.e. imports being much larger than exports, the more that the substitution effect dominates. This effect is convex in the degree of import elasticity, rising more than proportionately with the degree of imbalance in trade, and is exacerbated by the structure of the “reciprocity” that punishes more greatly bilateral trade imbalances. Because US trade overall is more balanced than many of the more extreme countries – despite the large US trade deficit – this convexity effect is “hidden” by aggregation.

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the convexity effects. Figure 2 shows the differential effects of low and high-magnitude trade elasticities on US GDP and how those effects magnify with the size of a country’s trade imbalance with the US: China’s immense surplus – with effects literally off the chart – is at one end and the Netherlands, which runs a deficit with the US due to LNG imports, is at the other end. Figure 3 better shows the consistency of these effects across countries by presenting the differential growth impact of elasticities (low-elasticity growth effect minus high-elasticity effect) versus the ratio of US bilateral imports over exports, with the trade imbalance represented by bubbles. The scattering of bubbles from upper left to lower right illustrates the convexity effect.

Which estimate is closer to the truth: the larger effects estimated with aggregate data? Or the smaller growth effects estimated by summing up individual country effects? The truth likely lies somewhere in the middle. At 145% tariffs, even mid-range trade elasticities push trade with China to zero, which is probably untrue given the number of products where China has made itself the sole or dominant supplier. But the convexity effect is real and suggest that one should take other aggregate estimates – like those from the Tax Foundation or Yale Budget Lab – with a grain of salt.

But there is another caveat to consider that argues in the opposite direction for all estimates, bottom up or top down: global supply chains are far larger and more complex than the periods over which the standard trade literature estimates for elasticities were calculated. As long-time readers know, Complexity cascades, lead to potentially large nonlinearities. I suspect that is more likely to manifest as highly volatile data this year on a quarter-by-quarter basis than a larger or smaller mean growth effect, but only time will tell.

The fiscal/growth trade off...

But what is the Trump Administration getting in exchange for a cumulative loss in GDP of about 1% over three years? A lot according to the bottom two rows of Figure 1. At lower trade elasticities, the “reciprocal” tariffs raise an additional $862 billion in revenue in their first year, and about 2/3rds that amount in subsequent years. That equates to 3.0 and 1.9 percentage points of GDP stripped from the fiscal deficit. For larger-magnitude trade elasticities the numbers are smaller –1.1 to 2.2 percentage points of GDP – but that also is in exchange for much more modest GDP losses (or in the summed calculations, positive contributions to GDP). Put in more standard fiscal multiplier terms, the three-year cumulative growth to tax burden ranges between –0.26 and –0.41 using the aggregate data and – astoundingly – positive multipliers of 0.12 to 0.51 using the summed country effects. Remember, none of these estimates include any potentially positive effects on aggregate capex from the incentive to build capacity in the US, which would make them even more attractive.

...Is a lot better than for income tax hikes…

How does that compare with the tax hikes that the Trump Administration would like to forego in 2026 by extending the TCJA? This is where things get interesting. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that expiration of the TCJA would raise Federal revenues by 11%, or about 1.8 percentage points of GDP. That’s at the lower end of Figure 1’s estimates for the Trump reciprocal tariffs. But what are the associated growth effects of an income tax hike of that size. A variety of studies suggest that income tax multipliers range from -2 to -3, an order of magnitude higher than those calculated for tariffs with the aggregate data. Corporate taxes, to which the TCJA was skewed, are at the larger-magnitude end of that those estimates.7 That would imply that the 1.8 percentage point reduction in the Federal deficit would come at a cost of between 3.6 and 5.4 percentage points of GDP! David and Christina Romer show those effects take place over a few years with most of the adjustment in the first two years.8

...But cannot replace the income tax

Though it should be obvious, I’ll state it clearly for the record: the tariffs may offer a better tax/growth tradeoff than a single income tax hikes, but that does not mean they can replace income taxes for anything near realistic levels of government spending. US government spending — $6.75 trillion, or 23.4% of GDP — is way too high and does need to be severely cut. But imports of goods and services, $4.11 trillion in 2024, total just over half of government spending. Especially when one considers that defense spending, if anything, likely needs to double, there is simply no credible way that tariffs can ever generate sufficient revenue to replace the income tax. The best that tariffs can achieve is to augment income taxes in a country that is on a deeply unsustainable fiscal path. My point in comparing it to the TCJA is to illustrate that tariffs are neither as crazy nor as growth negative as the consensus seems to make them out and indeed may be fiscally responsible given the US budget needs.

Reassessing the sanity of tariffs and their effects

The direct comparison with the TCJA suggests that the Trump tariff hikes may be far more positive than conventional wisdom holds or the markets’ response to their announcement suggests. As noted, this is not likely to be immediately apparent amid what I expect to be a very volatile year for data. But if it plays out according to my estimates by yearend or early 2026 the effects on US sentiment may be significant as it will operate through three channels simultaneously: (1) better than expected growth underpinning higher-than-expected returns to capital; (2) a sharp improvement in US fiscal fundamentals; and (3) a reassessment of US policy credibility.

All three channels are likely to be particularly strong in relative terms. Europe is especially at risk of disappointment given – in my view, unwarranted – market optimism over the sharp change in the direction of its fiscal and defense policies. I am working on an article specifically addressing those changes, but the headline summary is that it will do little-to-nothing to boost European potential growth while adding dramatically to European debt profiles, sharply increasing the risks of another European debt and EMU crisis.

But the relative growth channel likely will be strong across the board. Figure 4 shows the three-year cumulative drag on US trading partners’ growth if the full reciprocal tariffs are applied as announced at the end of the current 90-day pause. The largest effects are concentrated among East Asian exporters like Vietnam (VN, -11.2%!), Taiwan (TW, -2.9%), Thailand (TH, -2.8%), Malaysia (MY, -1.2%), China (CN, -1.1%), and Japan (JP, -0.4%). Despite USMCA, Canada (CA, -0.4%) and Mexico (MX, -0.9%) suffer significant negative effects, too. But the hit to many European countries is larger than the bars in Figure 4 suggests since potential growth is much lower in these countries. Ireland (IE, -2.9%), with relatively high potential growth, is by far the worst affected in Europe, but for countries like Switzerland (CH, -1.2%), Slovakia (SK, -1.0%), Hungary (HU, -0.8%), Austria (AT, -0.5%), Italy (IT, -0.4%) and Germany (DE, -0.4%) where potential growth ranges from 0.6% in Italy to just under 2% in Slovakia, the effects likely will be felt even harder as a share of income growth.

Figure 4 also illustrate how little tariff retaliation negates the US advantage. The three-year cumulative effects on the US (lighter blue bars in Figure 4) are small and, more importantly, positive! Figure 5 decomposes those effects into the hit to consumers and the (mostly) offsetting net export effects. Only China, where total cumulative effects on GDP are estimated to be positive, has any significant impact on US consumers. That does not mean that no US trading partner has leverage (as I discuss below), but it does mean that the relative economic effects clearly skew in favor of the US.

Notably, these relative advantages are before one considers their effects on investment, which again, likely favors the US. The trend of automated Localization and its effects on capital deepening has been core to my above-consensus estimates for US potential growth and neutral real interest rates for the last decade. Tariff policies only reinforce a trend that already was strongly benefitting the US relative to other economies. Not only do US tariffs reinforce the natural trend of reindustrialization in the US but, at the margin, they disincentivize capex in US trading partners by decreasing their capacity utilization. That may not last for US allies if the aim of US “coercive” tariffs on them is to encourage the formation of a bloc that excludes Chinese manufactures, but both the intent and success of any such US coercion remain in question at this point.

Tariffs effects on US fiscal revenues will be more immediately apparent, but given the now-dominant recession narrative, markets may need to regain their faith in relative US growth fundamentals before pricing a better US fiscal path. Reassessing US policy credibility will take longer after the shock of the last two weeks, but the improvement in the US fiscal stance, if accompanied by the return to trend growth that I project, will gradually repair faith in US policymaking. That will be even more true if, as I expect, the Fed holds the line on tariffs’ inflation shock.

Juggling falling knives

Despite my relative positivity on the US outlook, now is no time to catch falling knives, much less attempt to juggle them. Whether my analysis of tariffs having more positive than expected effects and the fundamentals of “American exceptionalism” proves correct or not, the perceived hit to American policy credibility in the last two weeks will take both time and evidence to overcome. And it isn’t over: the tariffs have only been paused, setting the stage for more drama over negotiation and brinksmanship through at least midyear. Against that backdrop hangs in balance the two biggest questions determining the trajectory of the US dollar, relative asset prices and global risk premia: Has deleveraging run its course? And are we on the precipice of a larger asset allocation shift away from the US?

The answer to both questions is difficult. Positioning surveys are notoriously unreliable, lagged and often biased to US asset managers. The question is further complicated by what deleveraging means: Is it merely a reduction in leverage? Or a move back to benchmark? Given the size of price adjustments in the last two weeks, the former may be near its end, but the latter definition, given the duration of US outperformance since Covid, implies sustained US dollar and asset underperformance.

Assessing the more serious threat of reallocation away from the US is complicated by two factors: the potential for sovereign interference and the real problem asset allocators face of “into what?”

Fears of the former, particularly Chinese reallocation of their reserves away from the dollar or US Treasuries, has been a large driver of the blowout in US yields and fall in the dollar in the last week. While China’s reserve pile is large enough to play the role of mischief maker, the real risk to the dollar and US asset prices comes from US allies. The most worrying development in the last week was French President Macron’s Fredo-like encouragement of French firms and asset managers to suspend investment in the United States.9 Not only does it imply that the far larger fire power of European pensions and insurers might be in play but it would be a dangerous escalation of the rising tension between the US and its allies that should increase all risk premia, not just those on US assets.

But the real problem for allocators intent on US divestment is what to buy instead. The only market close to large enough is the euro area. Yet, as I alluded above, Europe has serious problems and faces worsening fundamentals in a trade war with the US amid an unresolved kinetic war on its border. Further there is the simple question of accounting identities: European (and Chinese) savings surpluses – i.e. capital account deficits – must go somewhere; likewise the US savings (aka current account) deficit must be funded. There is one variable that can adjust to equate the two sides if the savers are intent on US divestiture: the US dollar. Yet a weaker dollar would only reinforce the likelihood that the Trump Administration’s tariff policies will be successful.

That conundrum, the chaos of Trump Administration and the palpable umbrage of US allies, particular Europeans, makes me cautious on being a structural US dollar bull for the first time in over a decade. As should be clear from my framework and analysis above, that does not mean that I’ve lost faith in the fundamentals underlying a strong US dollar. But I have a healthy respect for Keynes’ aphorism that markets – and in this case, the White House – can remain irrational longer than you can remain liquid. There is no greater source of irrationality, even in finance, than nationalism.

I ultimately expect my views on fundamental relative value – i.e. a stronger dollar and a narrowing of US risk spreads relative to their European and Japanese peers – to be validated by fundamental developments, but that may be a long time coming. I see little risk reward in trading the dollar in either direction until we see clearer signs that deleveraging is complete and that an asset allocation shift from the US is (or definitely is not) underway. Similarly, despite the extreme widening in US swap spreads, I would be cautious in re-engaging in the received US/paid French swap spread trade that I recommended in La Cosa Nostra Americana. The stall in US spread widening and incipient signs of French OAT underperformance are worth watching carefully that a turn may be in the offering, but the current risk environment is prohibitive and there likely will be plenty of time to re-enter that trade as the reversal of the last two weeks’ move will not be as quick.

Look where the crowd is running from

In the meantime, my strongest view for 2025 – high volatility of volatility – remains as germane as ever. However, finding a vol of vol expression that offers value after two weeks of insanity is a serious challenge. At times like these, the most promising places to look for value is in the opposite direction the consensus is running.

The euro’s surge is the result of the EU being the only large, open capital account market that is not the US. But that rubber band can only stretch so far from fundamentals. Euro downside in the European crosses looks quite cheap. For instance, 1-year 10-delta EURSEK puts are trading at an implied vol that is only slightly above its median for the last decade and cheaper than 1-year ATM vol, yet Sweden has little debt, leading industrial, defense and tech sectors, and has all the benefits of the EU without the risks of the EMU. EURGBP 1-year 10-delta puts are nearly as attractive priced flat to ATM vol and in the 25th percentile of their 10-year history.

Alternatively, US rates markets are pricing a path of slow but steady rates cuts over the next two years. Yet, as I noted in Ball’s in your court, Jay, the Fed likely is hamstrung for at least the next six months by elevated consumer inflation expectations and uncertainty. By then, if my economic views are correct, there will be no cause for rates cuts and even potential for hikes. Hence, the only path that leads to rate cuts over the next year is a clear recession, in which case the Fed’s rate cutting path is unlikely to be slow. But swaption markets suggest unusually low probabilities of either “tail”: 1-year by 2-year forward receiver swaptions with a strike of -100 basis points that would payoff if the Fed cut more aggressively are trading at only a 38th percentile vol, while ATM payer swaptions that likely would increase in value if the Fed stayed on hold are trading at just a 28th percentile vol.

Appendix

The first-order simple model used to estimate tariffs’ growth effects result from negative income and positive substitution effects, that 100% of tariffs is passed through to import prices, and that effects occur over three years. Starting with the national income identity, the effects are given by:

Where a, b, g, c, and m are, respectively, the consumption (C), investment (I), government (G), export (X), and import (M) shares of output (Y) the economy, and D[ ] is the change in each due to new tariffs. Because inflation expectations are assumed to be stable, the change in import prices is seen as a real income loss by both businesses and households and the resultant changes in consumption and investment are assumed to be their first-order income effects occuring only in year 1 when the import price shock hits:

and

where MPC and MPI are the marginal propensity to consume and invest, respectively, and assumed based on the Economics literature to be 0.8 and 0.05, respectively; and are the import shares of consumption and investment, respectively, which are taken from US data for US imports and OECD averages to estimate effects on foreign economies from retaliatory tariffs applied to the US; and Dt is the change in tariff rates.

Substitution effects are modelled as the changes in net exports based on estimated import elasticities to prices, with short-run elasticities used to calculate year 1 changes in net exports and long-run elasticities assumed to be distributed evenly over years 2 and 3:

where is the retaliatory tariff imposed by foreign country f (assumed as equal to US tariff applied to country f).

Government expenditure on imports is assumed to be price incentive, hence is unchanged by tariffs.

Financial Disclosure and Disclaimer

The research, reports, and insights provided by Thematic Markets, Ltd are for informational purposes only and are not intended to constitute financial, investment, legal, tax, or other professional advice. The content is prepared without consideration of individual circumstances, financial objectives, or risk tolerances, and readers should not regard the information as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any specific securities, investments, or financial products.

Users of Thematic Markets, Ltd research are solely responsible for their own independent analysis, due diligence, and investment decisions. We strongly advise consulting qualified financial professionals or other advisors before making investment decisions or acting on any information provided in our materials.

The information and opinions provided are based on sources believed to be reliable and accurate at the time of publication. However, Thematic Markets, Ltd makes no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of the information. Markets, financial instruments, and macroeconomic conditions are inherently unpredictable, and past performance is not indicative of future results.

Thematic Markets, Ltd accepts no liability for any losses, damages, or consequences arising from the use of its research or reliance on the information contained therein. Readers acknowledge that investment decisions carry inherent risks, including the risk of capital loss.

This disclaimer applies globally and shall be enforceable in jurisdictions where Thematic Markets, Ltd, a company incorporated and based in England and Wales, operates. Readers in all jurisdictions, including but not limited to the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, European Union, Australia, Singapore, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, are responsible for ensuring compliance with local laws, rules, and regulations.

By accessing or using the research provided by Thematic Markets, Ltd, users agree to the terms of this disclaimer.

As noted in the introduction, I initially expected markets to react to Donald Trump’s election in 2016 much as they have this week, especially given that it surprised most. But since Covid I have warned about rising non-quantifiable tail risks associated with a loss of faith in many Western policy institutions, both supranational and sovereign, including the US. My “Complexity cascades” series at Barclays (available to subscribers by request) in the summer of 2020, Global entropy: enter the dragons (November 2023), the May you live in interesting timesseries of 2024 Leitmotifs (January 2024) and my Leitmotifs for 2025 (January 2025) all delve into the risks presented by loss of the post-War liberal order and, along with La Cosa Nostra Americana (March 2025), a framework for analyzing its successor.

Yes, President Trump has hinted that he may seek to run again and there are proposals for how he might do it, but realistically it would be difficult to overcome the 22nd Amendment, and at 82 in 2028, would President Trump really want to run again and would Americans elect him after the experience of Joe Biden? See “How Trump Could Snatch a Third Term – Despite the 22nd Amendment,” James Romoser, Politico, 31 January 2025; and 22ndAmendment: Two-Term Limit on Presidency, National Constitutional Center (website, as of 20 March 2025).

“Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Adjusts Tariffs on Canada and Mexico to Minimize Disruption to the Automotive Industry,” The White House, 6 March 2025; and “US auto industry could be collateral damage in Trump’s trade wars,” Paul Wiseman & Alexa St. John, Associated Press, 1 March 2025.

“The Geography of Economic Development,” Jeffrey D. Sachs, Naval War College Review, vol. 53 : no. 4 , article 8, Autumn 2000.

“David Ricardo, the Stock Exchange, and the Battle of Waterloo: Samuelsonian legends lack historical evidence,” Wilfried Parys, University of Antwerp working paper 2020-009, December 2020; “Ricardo’s Classical Political Economy,” Karl Fitzgerald, Progress Magazine/Prosper, 23 May 2019; “How David Ricardo Became The Richest Economist In History,” Mark Skousen, Daily Reckoning, 22 January 2010.

That is a 1 percentage point move in import prices reduces import volumes by between 0.2% and 0.5% in the short run and 0.6% and 1.5% in the long run. Goldstein & Khan (1985) found import elasticities of -0.5 to -1.5 and export elasticities of 0.3 to 1.5; Hooper, Johnson & Marquez (2000) estimated long-run import elasticities for the U.S. at -0.8 to -1.5 and export elasticities at 0.6 to 1.2.

“Macroeconomic Shocks and Their Propagation,” Valerie A. Ramey, Handbook of Macroeconomics, Volume 2A, Elsevier, 2016.

“The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks,” Christina D. Romer & David H. Romer, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 13264, July 2007.

“France’s Macron calls for suspension of investment in US after tariffs,” Reuters, 3 April 2025.

Michael, so good to hear from you after all these years! Thank you for your kind words. AGI, aka the God machine, does have immense implications and unfortunately most of them are not benign. In the meantime, yes, the US and China seem to be galloping ahead of everyone else both in developing AI capabilities and in deploying them. That's why the strategic competition between them is so fierce: creating God is a winner-take-all event.

Another terrific piece and well explained. Thank you!